Rider and Rig: Where Is Karl?

Share This

As luck would have it, Karl Kroll was recently seen cycling through the neighbourhood, giving us the chance to chat to the long-distance bikepacker as he puts the final pieces down for his mammoth Americas Bike Trip jigsaw. Over a local campout and an ice cream float, we talk about everything from Ecuadorian Dangle Llamas to packing bearings with bananas, bikey family heirlooms to triple-padded bar-ends, along with unfortunate finds in the Copper Canyon and running a YouTube channel. Plus, check out his complete gearlist honed after 31 months on the road…

I’ve mentioned before how living in Mexico has afforded me wonderful opportunities to meet passing bike travellers, such as dogpackers JC, Zaïna, and Basquiat, Salvadorian Andrea and US-born Jake, or ‘almost-Alaskans’ escaping winter Chris and Amanda.

I try and celebrate these encounters with a local overnighter; after all, what better way to hear travel stories than around an al fresco dinner, or whilst packing up in the morning sunshine, charged with excitement for the road ahead.

Karl Kroll and I had the chance to share such a campout. Being the dry season here in Mexico, we bonded over sugary aguas frescas and nieves – fruit juices and sorbets – and even both at the same time, chatting over pints of horchata mixed with ladlefuls of icy cactus fruit, Oaxaca’s glorious take on an ice cream float.

The ride I’d planned headed out beyond the Árbol del Tule towards Tlacolula, where we could pitch our tents in a scruff of land amongst organ cacti and prickly pears. From there, I’d bid Karl a Buen Viaje and turn homewards, leaving him to continue towards Chiapas on the Trans Mexico Sur (and Costa Rica beyond). Our route also took us through the Zapotec pottery village of San Marcos Tlapazola, where we were treated to a demonstration on how barro rojo is made, using clay dug out from nearby hills – a process that’s largely unchanged in millenia. With some gentle encouragement, this even resulted in Karl’s acquisition of an unexpectedly large coffee goblet for morning brews to come. Would it make it all the way back to his home in Minneapolis or be smashed to smitherines, somewhere on Central America’s rugged dirt roads, I wondered?

Read on for a few of the stories behind Karl’s 31-month, 28,139-mile trip (as tallied yesterday night, when he updated me from a Nicaraguan fire station where he was camping), a journey that has seen him ride north and south, in his efforts to cover the length of the Americas in uncertain times. And, watch a few of his favourite Youtube videos below.

First things first. Can you share the shape of your Americas trip, broadly speaking? If I’m not mistaken, it’s become a bit of a jigsaw puzzle to complete, given the way world events have unfolded over the last few years.

I began my trip Northbound from Ushuaia, Argentina, in January of 2019, following a number of established bikepacking routes and trails found along the way. Note to readers: This is probably the wrong direction to start a trip in Tierra del Fuego unless you are a masochist and enjoy riding directly into some of the strongest winds in the world, known as the “Roaring Forties.”

I rode the spine of the Andes over the next 14 months across South America via Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. I had just crossed into Central America and made my way to Costa Rica in March of 2020 when international borders started closing all around me. It was a very interesting experience to be in foreign country at that time. After meeting some Europeans who were already stranded without a way home, I made the difficult decision to put my travel dreams on hold. I made it to the somewhat random town of Palmar Norte, turned my handlebars toward the airport, and flew home to Minneapolis, Minnesota.

After the planned break of weeks turned to months, I set my sights west and rode the American section of the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR). My thought at the time was that the Great Divide would be the American portion of my trip, something I had long dreamed about while in South America. The famous route and films such as Ride the Divide were largely the inspiration for my first bikepacking trips. As I reached the Antelope Wells border station, I was told it was still closed, and I wouldn’t be able to cross as had been my intention. Not to be discouraged I rode to Arizona, thinking I’d ride the AZT and cross at a larger border station. Broken chainstays and a break with a friend in Phoenix ensued. While Andrew from Bike Fab Supply graciously fixed my bicycle, I researched and found that Central American travel involved a lot of PCR tests and that Belize was still not open. I decided to wait on the trip south until things were more conducive to normal travel.

After the GDMBR, a long winter turned to summer, and still the friendly neighbor to the north had closed borders to us Americans and the rest of the world. I started to wonder if completing the trip would ever be possible. While on a climbing trip in Montana, I reached the top of a peak and was surprised to have signal. My phone blew up and I received messages that Canada planned to open borders on August 9, 2021. Knowing this was the last opportunity to ride in the far northern latitudes of Alaska and Canada before another winter, I packed up my bike and put tires on the ground in Deadhorse, Alaska, as one of the first Americans to cross that border in nearly two and a half years.

Now heading southbound in the cold and with snow falling the first three days of this new leg of my journey, I was ecstatic to be back on the road. In this glee-filled state, I made the decision to ride across the United States again. Because I had already ridden the Great Divide, I would use the opportunity to tie my home state of Minnesota into the trip, willfully ignoring the fact that this would mean cycling roughly half of Canada before descending down through the middle of the US.

My final destination became that same random town where I’d stopped riding in Costa Rica in 2020. It seemed fitting. As the overused saying goes, “It is not the destination but the journey.” My trip would now be a journey to a place in between the standard destinations.

Due to COVID-19, you left home twice. Your route the second time round seemed especially offbeat and interesting. What can you tell us about it?

Because bicycle travel provides such a beautiful perspective of places foreign, it only seemed reasonable to take the opportunity to experience the familiar from a bicycle to broaden my perspective of my home state of Minnesota. With the decision made, my first destination was Grandma’s house, which sits in a tiny town just a stone’s throw from the Canadian border with a booming population of 707. After two months of riding, the feeling of surprising the tiny border crossing and suddenly showing up to everything familiar was a trip in itself. The homemade meals and days spent with a loving grandma were more fulfilling than I could have imagined.

The states below Minnesota (Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas) normally don’t find their way on Ushuaia-Deadhorse trip itineraries. As I travelled south into the “Bible Belt,” I felt more like a stranger in my own country than I ever had in my time in Canada. The friendly and interested locals always made me feel at home, but I learned firsthand how real “food deserts” are as I hopped between different dollar stores all selling the same processed food, unable to find any real nutrition through the area. A low was when I found myself celebrating the veggies on top of a Subway sandwich.

My few days on the Arkansas High Country Route in the Ozarks were a highlight through the Southern US, after which I decided to stick to my plan of riding the Copper Canyon of Northern Mexico and therefore would cross nearly the entire state of Texas to arrive at the border of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Days of riding through high fence ranches and extremely limited wild camping were difficult, but Austin, mom and pop donut shops, and Big Bend National Park were highlights before crossing the border into the promised land of Mexico.

You mentioned you also rode through Northern Mexico’s somewhat notorious (but incredibly beautiful) Copper Canyon. Can you share some details?

Wow, so much to unpack with Copper Canyon! I had been intrigued by the Indigenous history of the local Tarahumara people after first reading about them in Born to Run by Christopher McDougall. The Tarahumara, or more properly called Rarámuri, are the local Indigenous group and are often referred to as the “running people.” This is due to the ridiculous terrain in which they live, varying from the rim at 8,300 feet (2,540 meters) and the valley floor sitting at 1,800 feet (550 meters). This makes it deeper than the Grand Canyon, but instead of it just being one canyon, it’s many, making it the perfect place for an Indigenous group to be largely unbothered by outside influences and a place which has historically hidden bandits and those seeking to be outside the influence of the Mexican government—something which makes the canyon infamous to this day.

One fine day while cycling through a snow/rain mixture along the canyon rim, I was desperate for a place to get out of the elements. Seeing a boulder field, I figured I could find someplace dry. After a few minutes of searching, I came across a cave created by some giant house-sized boulders and marvelled at my luck and entered, only seconds later to be confused by the five giant garbage bags I encountered. As I walked up to them wondering what they could be, I caught one whiff of the universally known skunky smell of cannabis and turned on my heels. I knew I didn’t want to be around when whoever had put it there came back, and if someone was watching, I didn’t want them to think I was overly interested.

I continued cycling and the storm progressed into near white-out conditions until I descended the 5,000 feet to the town of Batopilas, where the snow turned to rain. Along the descent, I passed my third and fourth vehicles of the day, two nearly brand new pick-up trucks full of men ascending into the storm. In the beds of one of the trucks, I noticed an identical giant garbage bag to the ones I had seen earlier. While exploring the town the next day, a casually dressed man with a radio greeted me and said in Spanish, “You’re the guy we saw yesterday.” Turns out that there had been some communication among the cartel about my whereabouts.

Semi-threatening “police” with AK-47s—who weren’t actually police—were the norm in some villages. But the majority of my experience in the wilderness of the canyons was positive. Endless foot trails and roads without any traffic were the norm, friendly people thrilled to see someone traveling through the beautiful place they call home. After one day-long climb where the only traffic I crossed was a small group of Rarámuri on foot, a local insisted I stay in his home because of the snow still covering the ground. Over a coffee, I told him there weren’t many trucks on the road. He responded, “Solo un o dos por semana,” meaning only one or two per week. Which is exactly the magic which sums up my experience bikepacking in the canyons.

I read on your Instagram account how you’d recently decided not to stay in any hotels, in an effort to reconnect with nature and the people around you. How did that work, and what did you learn from it?

The decision for me to stay away from hotels is an easy one. Cycle travelling for me is about learning about the places I am traveling and about myself. In certain places, it’s easy to find “wild camping,” but it’s more difficult in others. In the more populated areas, it involves getting outside of your comfort zone and asking locals if there is a safe place to pitch a tent. What generally follows is some curiosity about the trip, then questions about gear. I invite them to come see everything as I set up camp; people are fascinated by my multi-fuel stove, and a true cultural exchange ensues.

Apart from these conversations with locals being my main form of Spanish class, I’ve learned about the typical local food (often being offered a sample) and local traditions. I’ve helped pick potatoes behind a team of oxen and learned about area trees and edible mushrooms. The locals are always curious about the bicycle, marital status, and life in the United States, so I come away with an entertaining evening.

Also, something fun I’ve started doing when people find “wild camp” in the morning is inviting them for a coffee. I’ve found nearly everyone loves coffee, and it’s the perfect way to start a conversation and show them that you mean well. I think it’s important to note that with “wild camping,” meaning camping in an unofficial camp site, I always try to leave it better than when I arrived, meaning pack out what I brought in and if possible find a piece or two of garbage to improve the area.

Was YouTubing something you did before you left or intentional for the trip? What kind of recording gear do you carry?

With bikepacking videos being such a large inspiration for me (such as those by the late Iohan Gueorguiev), I knew I wanted to make my own not long after my first big trip. I set out in 2018 on a trip from Warsaw, Poland, where I was living at the time, to the Republic of Georgia and filmed the trip. Afterward, while trying to edit the mess of footage, I realized there’s a lot more to filming and storytelling than just bringing a camera and occasionally turning it on. That footage is still sitting unedited. Maybe sometime I will find the patience to get back to it.

On my next trip through Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, I filmed the trip with a friend and was hooked on the storytelling experience. It was wonderful that I found something to be passionate about but terrible that my kit suddenly got 30% heavier.

Now, I am carrying a camera (Sony Rx-100), Gopro (10), and drone (Mavic Air 2) along with all the equipment needed to keep them charged. When you add an external hard drive to back up all the video and a laptop to edit, gone are the days of lightweight riding.

Does it take up much time? How do you find getting the ‘experiencing’ vs ‘storytelling’ balance?

Filming does take up a ton of time, but if it is something you enjoy, as I do, I find some of my favorite days riding are actually the days when I spend the most time filming.

I know that sounds strange, but a huge reason a lot of us enjoy bikepacking is for the scenery. Filming gives me the permission to really slow down and take it all in, albeit often through the lens of my camera. Rather than just whizzing by some tree or flower, I might stop and take a video and search all the fine details to share with the audience. For me, this is what makes filming fun. And although editing can be a huge pain, reliving the emotions of a trip can be a very rewarding experience. Just like keeping a journal, all the tiny things that happened between the main scenes come flooding back.

Any favourite videos you’d like to share?

This video from Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan is still one of my favorites. With my first ride over a month just under my belt, I was just experienced enough to get into trouble. John Scully, a good friend from university, was flying over to join me for the trip and we ended up making a pretty alright team with a great sense of humor. John would later accompany me through Bolivia on a mountaineering/bikepacking mission that has yet to be edited.

Another from South America would be this episode from Southern Chile around Torres Del Paine National Park. The scenery speaks for itself, and I’m pretty proud of my improvised fix of a broken cassette. I didn’t know it at the time, but I would ride a couple of weeks on that cassette without issue before having it replaced.

And if you’re interest in the gear I’m carrying, check out this guide covering what kit I used for the GDMBR. Rather than being the typical video promoting going ultralight, it demonstrates that one can use fairly standard gear to ride the route. Because of this, I have received some great feedback from people who appreciate this atypical approach to our sport, one that can sometimes seem elitist, with carbon fiber bicycles and uber-expensive frame bags.

Talking of gear, I love the weathered and very distinct look of your setup. In terms of bike stuff, what’s cut the mustard and what’s fallen by the wayside? Oh, and I think we need a backstory on that sun faded handlebar bag…

It takes a lot of work to keep all my gear looking very worn! I’m aboard a 2015 Salsa El Mariachi cleverly named “The Pony.” The name wasn’t intentional but just something that occurred during my first tour. It was pretty much stock until this most recent leg of the journey. Rebuilds of the front suspension were becoming more and more frequent, so I took the opportunity to get a second-hand Whiskey Carbon Fork and enjoy the fully rigid feel. I’m riding tubeless on Maxxis Ardent 2.4” tires, which I find give me ample cushion/float for rough/soft terrain. My front tire has also lasted since starting in Prudhoe Bay, and now it has become a point of pride to finish the trip with it. I am now on my third rear tire, which is a huge improvement of the random assortment of rubber I was using in South America, sometimes going through a tire in as little as 2,000 miles.

The handlebar bag is a family heirloom of sorts. While growing up, my family would spend a day or two every year riding one of the rail-to-trail routes with which Minnesota is blessed. My dad always used the bag on our trips, so I grew up seeing him pull every tool needed to make a repair on the bikes. To my young eyes it, was a magician’s hat. Recently, I asked my dad where he got it, and it turns out it was a garage sale find.

When I moved to Europe with the intention to start bicycle touring, I asked my dad if I could have the bag, to which he happily accepted. Now, this 30-year-old (estimated) “Cycling Pro” bag has accompanied me on all my journeys and been patched and had the zippers replaced too many times. The mounting bracket has been welded three times and I’m constantly wondering when will be the next. Far from the perfect handlebar bag for the job, it has taken on a life of its own and seems to be yearning for an easy life of retirement once this trip is over.

Almost every other component has been replaced at least once, with my handlebars, headset, and front brake being the only original components on the bicycle. My derailleur was destroyed by an unfriendly rock while descending a volcano in Argentina, and I had the pleasure of riding the next four days on the ruta 40 single speed, enabled by the Alternator dropouts.

I seem to have a thing for destroying bottom brackets, something I learned on my first big tour while in Turkey and Georgia. I had been nursing a bottom bracket when it completely seized up in the mountains during a storm. Luckily, its terrible condition meant I could disassemble it with a leatherman. The ball bearings all fell into the mud, and trying to re-pack them wasn’t an option with the bearing race being totally non-existent at this point. I looked at what I had and tried to think of a solution. I would take my Coke bottle cap and cut it to make a bushing. Luckily, it was just the perfect size to fit around my crank. Now, I just needed some good lubrication for my bushing and I would be off and to the races. Finishing a banana, I thought, “Perfect!” I took two banana peels and smashed it into my bottom bracket around the crank. Maybe not the Park Tool approved method, but the repair got me to Tbilisi, where I was able to get a new bottom bracket.

The Pony Highlights

- Frame and fork: 2015 Salsa El Mariachi and Whisky Carbon Fork

- Rims: Front Stans ZTR and Rear DT Swiss ER 1600

- Hubs: Front Formula and Rear DT Swiss 350 Spline

- Tires: 2.4” Maxxis Ardent setup Tubeless

- Handlebars: Salsa 170mm Flat Bar with “custom” Romanian bar ends

- Stem: Salsa Guide

- Headset: Cane Creek 10

- Crankset: Shanmashi Andeshunk 3 speed

- Cassette: 11-36 10 Speed Shimano Deore

- Derailleur(s): Shimano Deore front and Rear

- Brakes: Hydraulic Shimano M445 w/ 160mm rotors

- Shifter:Shimano Deore

- Saddle: Brooks B17

- Seatpost: Truvativ T20 offset

- Pedals: Crankbrothers Double Shot

- Frame Bag: Ortlieb 6L

- Front Bag(s): Cycle Pro Front bag and Revelate Designs Sweet Roll

- Rear Bag(s): Itiwit 20L backpack and 10L Dry Bag

- Accessory Bag(s): 2 0.5L, 1 Gas tank, and 1 feed bag all Btwin, Unknown Brand for Multi-tool Accessory Pouch

- Other Accessories: Ecuadorian Llama co-pilot

Looks like The Pony has accrued some battle scars. How’s it faring?

“The Pony” has treated me very well overall, but we have had some mishaps. In 2020, after riding the GDMBR and learning that the Antelope Wells border crossing was closed, I was heading to the AZT, as mentioned above. During the early hours of my ride, I suddenly had some bad tire rub and stopped to sort it out. My mind was blown by what I found. My chainstays were both broken, one so severely it was hanging freely and rubbing against my tire. In the middle of nowhere, I started preparing to make a repair when a proud rancher of Mexican heritage showed up. He offered a ride to the highway where a friend came from Phoenix and drove me to the city. In Phoenix, I spoke with Andrew of Bike Fab Supply (a supplier for many of the best frame builders out there) and he quickly agreed to do the repairs himself, below cost, just to help out a cyclist in need. Thanks, Andrew!

I would say that is the end of my frame issues, but recently in El Salvador, I broke my seat stays! I had just thrown on a small pannier with my partner’s old drivetrain and some other random items such as that ceramic coffee mug I bought in Oaxaca (not very ultralight btw) and rode a bikepacking alternate route I found which runs parallel to the popular tourist paved bus trail, “Ruta de los Flores.” Upon reaching the coast and its paved roads, I noticed my bike felt sloppy and I chalked it up to the pannier, thinking to myself, “Panniers, never again…”

The next morning, I went to tighten my Old Man Mountain rack to see if that would fix the sloppiness and was stunned to see a repeat of the chainstays. I made a quick repair with some cordelette (thanks Juan) and a tent stake and laughed at my stupidity as my bike handling instantly improved drastically. I rode the rest of El Salvador that way until Honduras, where a friendly warmshowers host and engineer put me in contact with a welder in a nearby town. Not nearly as pretty or sturdy as the work I had done in Phoenix by Andrew but enough to continue the trip without the fear of my rear triangle suddenly shearing off my bike on every bump.

How about those plush, sofa-like bar-ends and that Dangle Lama?

A lot of people ask about my enormous bar-ends. During my second big tour, I was looking for a way to adjust my position and picked up cheap steel bar-ends from Romania’s version of Walmart. A roll of bar tape later and they were getting pretty comfy. I thought, “If one roll of bar tape was good, how great would three be?!” and the giant bar-ends were born. Now, after a few years of abuse, they are looking pretty rough but still function as a great hand position for long days in the saddle.

My co-pilot who dangles off my front bag is a llama from Ecuador, a replacement for a Peruvian llama who lies on some dusty road in the Andes. I have a 6L Ortlieb roll top frame bag. A feed bag as well as three other small 0.5L bags from Decathlon to keep small items such as my multi-tool organized and handy.

I think like a lot of riders out there, I started with too much gear and therefore I had two rear panniers while riding through South America. After riding the GDMBR without panniers and enjoying the simplicity, I decided to try and keep the system for long-term travel. My main bag is a 20L waterproof backpack from Decathlon that’s actually made for sailing. European readers should be familiar with Decathlon for providing relatively good quality gear for decent prices. The waterproof backpack is wonderful for my trip because whether it’s a trip to the grocery store in a city or a two-day hike into the mountains, I can just take it off my bicycle and have a fully functioning backpack. When a day calls for some serious hike-a-bike, I can also unload the bicycle and wear the pack.

You mention your fighting weight – bike, gear, and a typical payload of food and water – is around 45kg. Can you share your hallowed gear list for such a long journey?

BIKE GEAR

Old Man Mountain Divide Rack (Made in USA version)

Crank Brothers Double Shot pedals

Brooks B17 Saddle

Romanian bar ends with 3 rolls of bar tape

Helmet

Crank Brothers M19 Multitool

Leatherman Surge, Heavy but I use it all the time

Lock: I use a long shackle masterlock which can fit around both of my chainstays (just like a dutch style wheel lock). I have a very fine cable which can connect this to my tent or a tree for some security.

BIKE BAGS

1992 Cycle Pro Front bag

Ortlieb 6L Frame Pack

Revelate Designs Handlebar Roll

Btwin 0.5L Seat Post and Top tube bag

Btwin ‘gas tank’ and Feed bag

Sleeping Bag: Decathlon 50F rated bag, I had a 15F bag from Alaska until Texas

Itwit 25L waterproof backpack on my rear rack

Itwit 10L drybag for food

Small bag of unknown brand for Leatherman and Multitool

Locking aluminium Carabiners to restrain gear for bumpy routes

4 “roadside find” bungees to restrain the bags

CAMPING

Katadyn 3.0L Gravity Water Filter

Bear Spray for Alaska/Canada and the GDMBR

Small Pepper Spray: for the meanest of dogs, rarely used but much better than throwing rocks IMO

48 oz Giant Nalgene, and 2 1L bottles

Long handled Spork

Tent: Big Agnes Copper Spur 2

Klymit Insulated Ultralight Pad

Inflatable Pillow

Stove: MSR Whisperlite

Bottle of Alcohol hand Sanitizer for clean priming of stove, and washing hands

1L fuel bottle

Bic lighter

Silicone Collapsible Travel Cup and Ceramic mug from Oaxaca

Walmart $0.50 plastic Bowl

1L cooking pot with 0.3L frying pan lid

Netted shopping bag, great for foraged finds

Collapsible fishing rod: A cheap one because it will be broken

CLOTHING

Shoes: Pearl Izumi X-Alp Divide

Pear Izumi Leg warmers

Banana Shirt: Bought in Vietnam during a motorcycle trip.

Long Sleeve Sun Shirt: Good for buggy campsites

“Dressy” short sleeved hawaiian/fly fishing shirt

Zip-off pants w/ zippered pocket

Dynamos zippered pocket yoga shorts (my riding shorts)

Wool Boxers for camp

2 pairs of unpadded compression boxers for riding

2 pairs of long lightweight defeet socks (Kuat Racks)

1 pair of midweight wool socks

1 pair of heavy wool socks

Rocky Mountain Hardwear Puff

Colombia Rain Pants

Rocky Mountain Hardwear Rain/Wind jacket

Baseball Cap with sun flap for days off the bike

Forclaz “Zero-Sole” style sandals for camp

ELECTRONICS

Samsung S9 (OsmAnd for offline Navigation)

Wireless headphones

BD storm Headlamp

NiteRider Lumina 1200 riding light

NiteRider Omegas 330 rear light

Anker Powercore 19200mah power bank (charges in 1.5 hours)

Anker 5 port wall charger

Various USB cables

REPAIRS

Small bottle of Oil, refilled from auto/moto repair shops

Small tube of white grease

Tire Levers: Park tool blue

Shrader to Presta Adapter: nice for setting up tubeless remotely

Tubeless patch kit

Voile Strap

Sewing kit

Small length of chain with 3 quick links

Extra brake pads, around 4 sets depending on country and availability

2 tubes with locally sourced “Thumbs up” patches

Extra Bottom Bracket

Spare cleats

~5 zip ties, 1 roll of electrical tape, and a small amount of gorilla duct tape

Small tubes of Shoe Glue, super glue, and Rubber cement (for patching air mattress)

ODDS AND ENDS

Cosmetics: Toothbrush, dental floss, Sunscreen, Face lotion, and lip balm

Ear plugs and eye cover for less than ideal “camping” spots

Passport w/ Pen for filling out forms if needed

Trip stickers – To give to people met along the way!

Sunglasses

VIDEO MAKING GEAR

Camera: Sony RX100 VII

Drone: DJI Mavic Air 2

Samsung S7 as designated drone phone, and backup of offline maps

Gopro: Hero 10

Small tripods for both the Gopro and Sony

Huawei Matebook, not currently working

4tb My Passport external hard drive

LOTS of 256 gb micro SD cards, I have grown to like Samsung

USB SD card reader for backing up footage

How much of your trip has been solo? Is that something you’ve grown to prefer, or is it just the way it’s worked out? How does it feel to be finishing off your ride with your partner?

Of the more than two years of riding during this trip, approximately six months have been with friends made along the trail and home. Most recently, as you hinted at, with my partner. I wouldn’t say it was something entirely intentional to do the majority of the trip solo, but with wanting to take time for filming, it’s important to have someone on the same page. I’ve grown to enjoy the benefits of solo travel, which include long periods of time in the meditative state I often find myself in while cranking on the pedals. The downside is finding yourself in a beautiful place and wishing there was someone to share it with.

Now, crossing Central America with my partner Rachael, it feels like the perfect end to the journey. It’s her first big bikepacking trip, and she is getting a well-deserved break after working as an EMT the last few years while earning her nursing degree. We have been pleasantly surprised that our route tastes match, and she is very patient with my filming.

Traveling with her has helped me be more in the moment. Her fresh enthusiasm for bicycle travel has helped fuel my own passion just at the end of a long trip when fatigue and looking toward the next big thing might have tempted me to rush through the amazing countries of Central America.

Dare I ask, but once you reach the fabled peninsula in Costa Rica, just a few weeks away, what’s next?

The BIG question!

I think I could fill an ever-growing book with all the places I want to cycle, but recently, places that hold a large chunk of my imagination are Mongolia and Japan. Yes, completly different locations and probably asking for different bicycles even. But both intereresting in their own way.

As far as another long-term bike travel destination, Africa has loomed large on my mind, in a large part because as I learn more about the continent, I realize how little I know about the different cultures, terrain, and people there.

In what must be a million memories, can you share a journey highlight?

At an elevation of 14,317 feet in the Southern Peruvian Andes, I came across a publito that I hadn’t previously noticed on my map. It was dark, and I was descending the muddy rutted road from the even higher pass. I spotted a small school with a light on and thought to ask about setting up my tent near the fútbol pitch. When I entered, I was surprised by the sounds of energetic children and was instantly swarmed and confronted by a continuous stream of questions as they looked at my bike and gear. I was confused why all the children were still at school. Later, I learned that their families live so remotely that they live at school Monday to Friday and walk home into the mountains on the weekends.

A short while later, the teacher informed me I could sleep inside a room if I wanted, which I graciously accepted in the freezing temperatures. Then commenced a night full of paper airplanes and all other sorts of crafts. No iPads or cell phones here. I must have folded 100s of planes before the night was over. I also introduced them to the paper snowflake, which was a big hit. We also held an impromptu Spanish, Quechua, and English language exchange in the hallway of the school, which also doubled as the busy airport for the paper planes. Well past their bedtime and mine, we cleaned up. Exhausted from the ride and the energy of the children, I went off to bed.

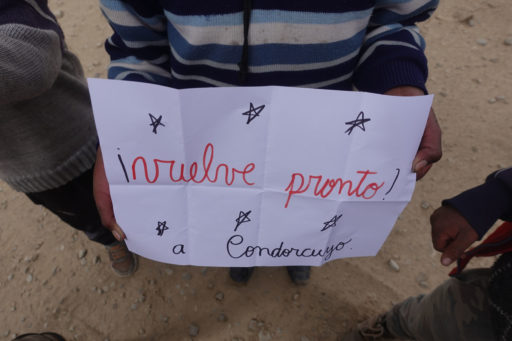

After some fútbol and more paper airplanes in the morning, I snuck off to buy them all cookies, which I smuggled to their teacher. They were served with breakfast (oops) and it was time for the school day to start. I set off on my way and was thinking to myself what a magical experience it was, and how I would love to spend a week there teaching and helping the children. Just then, I heard some yelling from behind me. Three boys were chasing me for the better part of my two-kilometer descent. They gave me a piece of paper from their teacher that said “Vuelve Pronto a Condorcuyo,” meaning “Return soon to Condorcuyo.” I rode on with a giant smile plastered to my, crossing a source of the Amazon just a few kilometres down the road.

Last but not least, it’s been two months since our campout. My most pressing question… do you still have the coffee tankard? Did it make it across Guatemala?

Lol, the coffee cup lives on! I always expect to find it broken but there must be titanium in the clay around Oaxaca. Buying it also seemed to have opened to souvenir floodgates, when I previously limited myself to a single magnet per country. Now, after the beautiful textiles of Guatemala, I am also carrying a handwoven bag and a pair of the iconic red pants from Huehuetango.

Thanks, Karl, for your fantastic and thoughtful responses. Let’s finish this off with a carousel of your images drawn from all these months of travel… Buen viaje!

Celebrate the end of Karl’s journey by following him on Instagram – Where Is Karl – or subscribing to his YouTube channel.

Related Content

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.