Inside Sven Cycles: Harmonizing the Past and the Present

Share This

Based on England’s South Coast, Darron Sven is a frame builder who’s been blending timeless designs and modern touches to create rolling works of art for more than 15 years. We sent photographer Tom Powell to spend a couple of days with Darron, and he put together a charming video portrait of Sven Cycles and an inside look at the bespoke builder’s work and guiding philosophy. Find it here…

The UK’s rich tapestry of bicycle craftsmanship is deeply rooted in history. It’s reminiscent of a bygone era of cycling when steel frames were meticulously crafted by some of the most skilled artisans in the world. Legends like Ephgrave, Hobbs of Barbican, Bates, Mercian, Clements, Claud Butler, Frank Lipscombe, and Witcombe etched their names into the cycling history books, producing frames that were not only utilitarian but masterpieces of design.

These British maestros were celebrated for more than just their steel prowess; their frames embodied a blend of geometry, lug work, light construction, and an unparalleled riding experience. They also benefited from the small island’s proximity to the finest steel tubing producers in the industry. This tiny realm remained a haven for producing the most exquisite steel tubing, a legacy that endures some 120 years later.

When rumours of a bespoke frame builder based on England’s misty Jurassic Coast reached my ears, I couldn’t help but be intrigued by the prospect of spending some time with a British artisan who was still weaving his craft in the age-old tradition of steel construction and willing to compete against the tide of assembly lines and quick turnarounds. That builder is Darron Sven, founder and owner of Sven Cycles, based in Weymouth, Dorset. It’s a town known for its sleepy seaside holiday ambiance as much as its attractiveness to the retired generations who flock to this quiet part of the coastline.

When I was back visiting the UK for the holidays and called Darron to make plans to visit a few days into 2024, he was anything but sleepy. And, by the sounds of it, he would certainly have a story or two to share. We made plans for me to stay the night and chat over fish and chips before visiting his workshop the following day.

Arriving at Darron’s terraced house, it was soon evident he was a man with fine creative taste. His walls are adorned with a well-curated collection of photographic prints, various artworks, and curios. Reclaimed flooring and a copper bathtub are the central features of his living space, and it became clear that attention to detail in design is something he lives for. He told me he’d had a previous life as a creative in London, and this was apparent in everything he did. He named artists from around the world for whom he’s currently making bikes in return for artwork—something that seems just as appealing to him as regular paying clients.

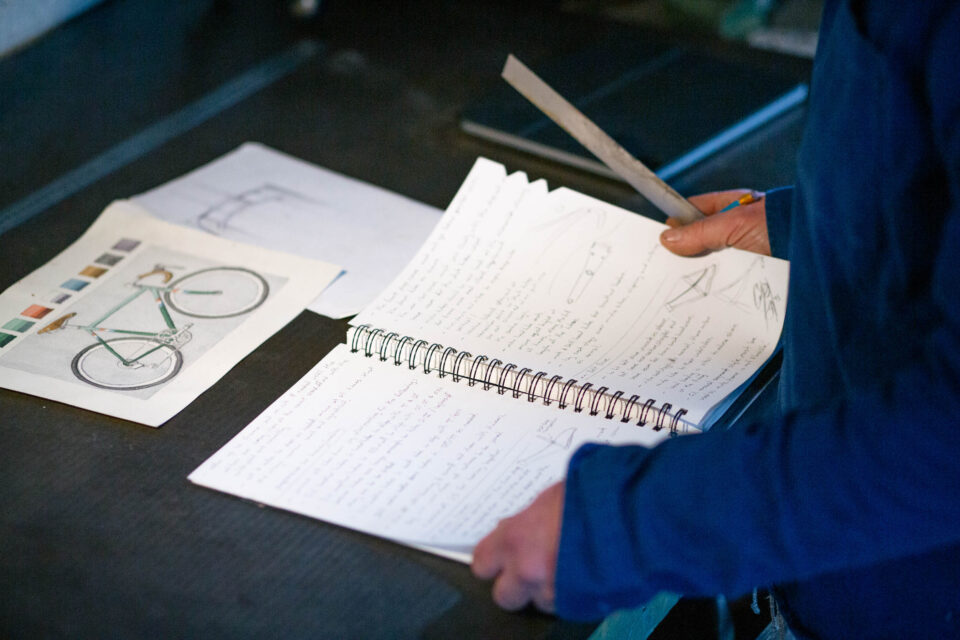

As I’d learn, his knowledge of the art world is extensive, and his approach to building bikes is no different. In his pursuit of frame building, he rigorously considers and agonizes over every detail as if he’s creating a painting or a sculpture. While we sat at his table eating fare from the local chippy, he remarked on all manner of things with his quintessentially British comedic pessimism. In a roundabout away, I came to understand that he’s a purist and loves bikes for their simplicity and beauty. He’s not impressed by or concerned with fads or trends, something reflected in his frame designs.

As for his taste in bikes, the mini velo is one of his current favorites, as is the mixte step-through with a curved top tube. He’s been refining these designs for a decade. His bicycle lineage dates back to the mid-80s when he would race cross-country mountain bikes. He explained that many of the things he needed in those days simply didn’t exist, which was his driving force to learn to weld and create them. His dad had always owned workshop spaces, so manufacturing and “having a go” was in his blood. Thumbing through his old photo albums, the bikes he was riding back then look very similar to today’s all-terrain bikepacking bikes, minus the disc brakes (and with more cut-off shorts).

While not specific to bikepacking, Sven’s bikes are practical and built for purpose. He’s as capable of making an electric bike for daily shopping as making a bike that will take its rider around the globe, and both would be constructed with the same detailed level of designed. His passion for all things bespoke drives what he does and the problem solver he is.

After a sound night spent in his spare room, surrounded by his daughter’s soft toy collection, we rode a blustery couple of kilometers along the beach to his workshop. It’s a space that’s tucked away amongst a shanty of cinder block garages and workshops and a place to keep his classic 1973 Citroen DS—another nod to classic design, although not quite as utilitarian as his bikes. Inside, the shop walls are adorned with various bits of cycling memorabilia that look like they’ve been there for years. Among the visual feast are old racing bibs hung from welding bottles, books about vintage cycling and Rene Herse, and various iterations of signage from the evolution of the brand. His space is lived in and used, and it’s something I felt very envious of.

The Sven workshop is not a production line. Rather, it’s a space for him to practice his art. Darron works at his own pace, and nothing goes out until he is satisfied. He takes great pride in thoughtfully working through the process of creating a beautifully finished bike. We sipped coffee from the local gas station while he gave me the tour and showed me some of his collection. As he worked, we talked over his process and what gets him out of bed and building bikes each morning. I followed up with him afterwards to learn a little more about his work, and you can find my extended interview below.

Tell us a little about how you first got into building bikes.

I was racing mountain bikes, and my dad always had garages and workshops and made things. I wanted a racing mountain bike, and I couldn’t afford one. So, we made one as simple as that. And it was just one of those evolving things from pulling bikes out of skips, welding bits onto them, and changing bits. Initially, I just made them because I couldn’t afford to buy the bikes I wanted, so I built something pretty close to it. They worked, and although they weren’t particularly refined, they’re still kicking around somewhere at my parents’ house.

What was the process of building the frames back then?

My dad had a fully equipped workshop and restored cars and things as a hobby. Everything was already there. It was a case of just measuring the bikes I liked and copying them, and then I just hand-painted them with an aerosol can. I think people get very wrapped up in the level of finish and detail on a bike. In reality, most of the time, if it’s designed properly, it doesn’t actually make that much difference as long as they don’t fall apart.

Have you always been a frame builder?

No. I’ve worked in the creative industry most of my life. Fifteen years ago, I moved out of London and wanted to do something with a little more substance. Cycling has always been part of my life, so it’s sort of evolved from there.

How does that creative background inform what you do today?

In a lot of what I build, whether people realize it or not, there are a lot of very subtle details, and I’m a bit obsessive about how I put things together and how they look as a complete bike. And I think it helps that I have a passion for color, detail, and design. I still do some freelance work, and the bikes are something of an escape for me. It’s really nice to make something that someone will ultimately keep for the rest of their life.

I’ve always been involved with stage set building. My first job was working at Shepperton Studios building sets. I’ve always made stuff, and that’s what drives me. I like creating things. I like coming up with an idea, doing a sketch in my sketchbook, and starting to put it together. It will always evolve as an idea, and you might even scrap it halfway through and go. Actually, that wasn’t such a great idea. Bike design is quite a known format, and mine are subtle changes and nuances you would put into a bike to make it ride a little bit better or be more suited to a certain style of ride, depending on what they want to do on it.

I love making bikes for people who love them, and I see them as one-off works of art. I see them as individual products. I’ve been known for making classically inspired contemporary bikes. We’re using very traditional manufacturing techniques but trying to use the best of what’s available now. My favorite form of construction is fillet brazing, which I use a lot, and I don’t think I’ve ever painted a bike the same color twice.

What’s your creative process with someone who comes to you for a complete bike?

People make an inquiry, we discuss the budget (because it ultimately is important), and then we work from that. We get very opposite ends of the spectrum where people will come to us because they know what we do, and it’s, “Hey, I would like a mini velo. I live in London, I’m going to go to the office, and I need to carry some files on the front of it. It needs to have light.” Some buyers give us a fairly basic brief and just let me build it. They leave it. Some people really have given me free rein to do whatever I want, including choosing the color. They do a bike fit or use one of our bike fit forms and then we send them an outline drawing of what the bike will look like. But the details will evolve as it goes along.

And then there are other people who give us a 10-page document of every single thing they want on the bike. Mostly though, I think somewhere in between is my sweet spot. The best way for me to work is someone will come to us and say, “I would like to do X, Y, and Z on the bike. What is the best solution?” And then we can go back to them with options based on tire size, whether they want mudguards, if they want built-in lights, and so forth.

I try not to overbuild bikes. If someone’s not going to ride at night, I’m not going to fit a dynamo and lights on it because rechargeable lights are great if you’re only using them every once in a blue moon. But if someone is building a bike they’re doing an expedition on, or they’re going to be commuting on daily, I’ll fit lights on it.

As for speccing other components, there are many incredible companies out there, but like anything, you’re paying a huge amount of money for a brand and a name in many cases. Some of them, without question, are worth it, but I think you can spend £15 on an, say, an alloy seatpost, and it’s great. Or you can spend £400 on a similar product, but is it actually going to do a better job than the alloy one?

And so, for cranks and brakes and things like that, it depends if someone has a bias towards incredibly low-maintenance, in which case we might build a bike with a belt drive, something I’m personally drawn to. And I think they’re great, especially with Pinion, but I like that if something goes wrong with a chain, it can be fixed anywhere—any bike shop, any scrap yard that’s got a bike in it, you can whack a chain off it, and you get your bike going.

I don’t like building things led by particular fashions. Some of the bikes I was building 15 years ago have become fashionable, but that’s simply because they’re practical.

Would you say your work is heavily influenced by classic bicycles?

I think Rene Herse, in particular, the bikes he built in the 1930s and ’40s, are influential. People are riding very similar bikes now, and he is just a genius. But then, you know, there’s very little that’s on a bike now apart from electronic shifting and such that wasn’t thought of and manufactured by the ’30s, but it’s evolved. Material choices, manufacturing ability, and techniques have changed to make them more efficient.

I’d say I’m quite influenced by bikes and design ideas from the past, but I do like it when people develop things that actually make total sense using the best of modern technology. If we’re going to build a bike and we’re going to spec it, any components I use, I will always do my best to use something that’s serviceable and maintainable, whether it’s classic or super modern.

If someone is ultimately investing in having a bike made, you want to know that if something goes wrong, they can take it anywhere, and it can be fixed. And that’s one thing I see within the bespoke bike world, which I think is lovely.

What do you think about the similarities and differences between bikepacking and bike touring, if any?

I think it’s the same thing! Bike touring or bikepacking. I don’t quite get the differentiation. If you’re traveling by bike, you might distribute your weight differently, and I think that’s where the evolution of more compact fitted luggage rather than big panniers over the side of your bike is a much better weight distribution.

I’ve got a book from 1985 called Bikepacking, and it has people on ’80s mountain bikes with saddle packs in Utah or somewhere. But I think it doesn’t matter what it’s called if people are going out and enjoying themselves. What I really like about the current era of bikepacking is that it’s made cycle touring fashionable. Before, it was old men with their Carradice panniers and baggy knitted shorts on.

I think it’s a really wholesome thing, if that’s the right term. It’s good if people are exploring, and you don’t have to travel around the world to enjoy it; you can just go 30 miles down the coast or inland and just stay in a farmer’s field. It doesn’t have to be hardcore in a bivvy bag in the middle of nowhere. It’s a nice way of getting around.

Life is bloody stressful. And if you can get on your bike, blow a few cobwebs out, and go and have a cup of coffee in the woods and make yourself a bacon sandwich in the morning, then bloody brilliant. I think everyone overanalyzes that you’ve got to do this or you’ve got to do that. But just go and spend 50 quid on an old mountain bike off Facebook and go and ride it.

Do you still love building bikes?

I fell out of love with it really badly a while back. I think Brexit caused a lot of issues for us because we had a terrific customer base in Europe, and it made us question how we could make it work commercially. I scaled everything back. We had four people here full-time producing quantities of really nice bicycles. But when I stepped back, I looked at the overheads of the business and realized that, yes, we were turning over good amounts of money, but the margin wasn’t there.

These days, I’ve got a few people who come in essentially as freelancers to help me, and then I do quite a lot of work myself. I’ve just kept it to a bare minimum, and I’m not borrowing. Scaling back has given me the creative freedom to indulge in what I really want to do and put care and attention into the bikes. So I’d prefer to build a dozen bikes here and just keep it more artisan and more specialist than produce on a large scale.

I just need to make stuff. And I love that bikes are useful and practical. That’s why I lean towards more utilitarian bikes because they get used regularly rather than polished and taken out on a rare day, like a lot of expensive bikes. We work on quite a few bikes for people with disabilities who can’t find anything that works for them, and that’s meaningful to me. I like getting people on the road. I built a tricycle for a guy who had a stroke, and he’s done thousands of miles on it.

Lastly, looking to the future, where would you like Sven to be?

We’ve explored a lot of avenues, trying to be more mainstream, trying to make it more accessible. But the reality of it is that we need to be at a certain price point to make it worthwhile. With the volumes we were making doing small batch, it just didn’t work. And now, moving forward, I just want to build bikes that are essentially rideable works of art, as I said.

Does it mean I want to put £2,000 airbrush paint jobs on them that you can’t touch? No. I just want to make very functional, well-considered bikes. Bespoke bikes are expensive, sure, but if you’ve got yours for 30 years and you get pleasure out of it, it’s still a good purchase.

For me, it’s never going to be a job that I can take big salaries out of or anything like that. But if I can feel like I’ve ended my week and I’ve done something productive and I’ve made something that someone is enjoying, I think it’s a good place, you know? I want to build bikes that I’m proud of, and I love when I get a postcard from someone who’s been somewhere on a bike or emailed to say, yeah, I still love my bike. It’s great. That’s what makes it all worthwhile for me.

You can find more from Sven on Instagram and at SvenCycles.co.uk.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.