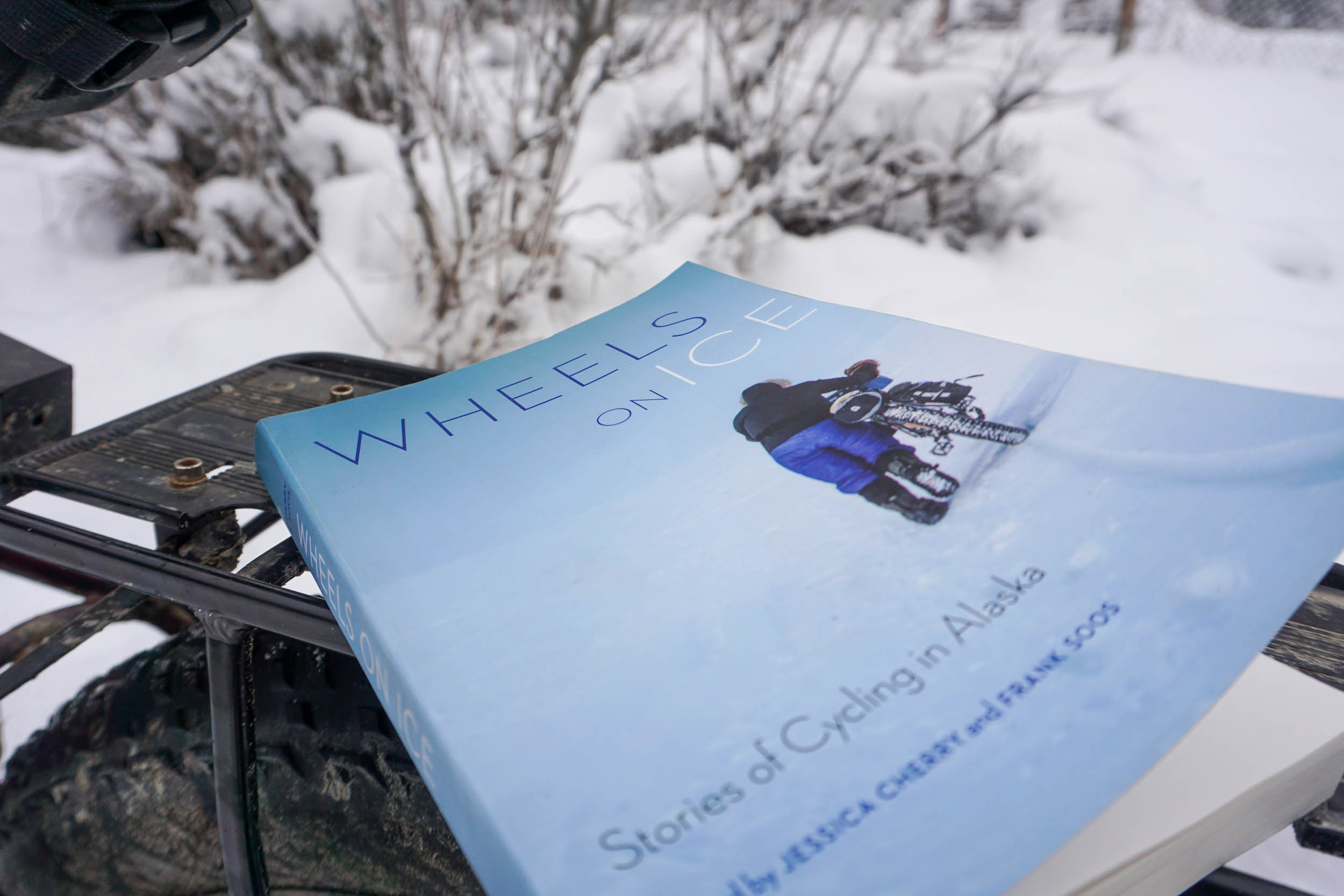

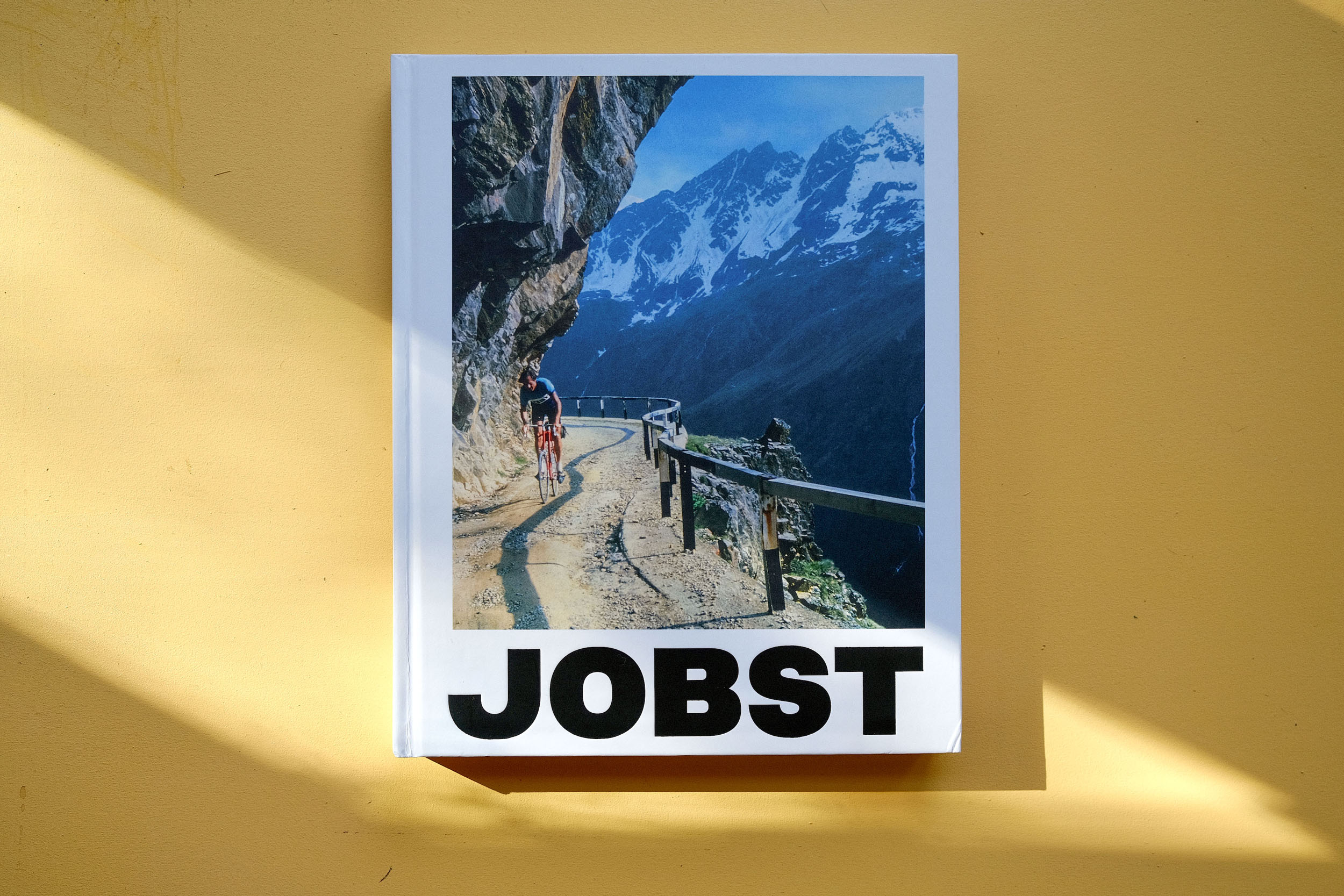

Wheels on Ice: Stories of Cycling in Alaska (Book Review)

“Wheels on Ice: Stories of Cycling in Alaska” is a 320-page book that dives deep into tales of bicycles in the far north from the gold rush of the late 1800s up to Lael Wilcox’s recent ride of every major road in the state. Alaskan cyclist and writer John Messick offers an engaging review of the collection here…

Words by John Messick, photos by John Messick and Jeremy Pataky

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a polar explorer. Unfortunately, I lived in rural Wisconsin, and my efforts to emulate Shackleton mostly involved snowmobile trails that skirted the edge of fallow farm fields.

In the absence of tundra, the bicycle became my tool for adventure. I pushed my parents to take me on The Ride Across Minnesota at age eight; at age 14, my dad and I biked to Maine. Much of my 20s were spent on a bicycle seat, with long rides through foreign countries punctuated by seasonal jobs to fund my trips.

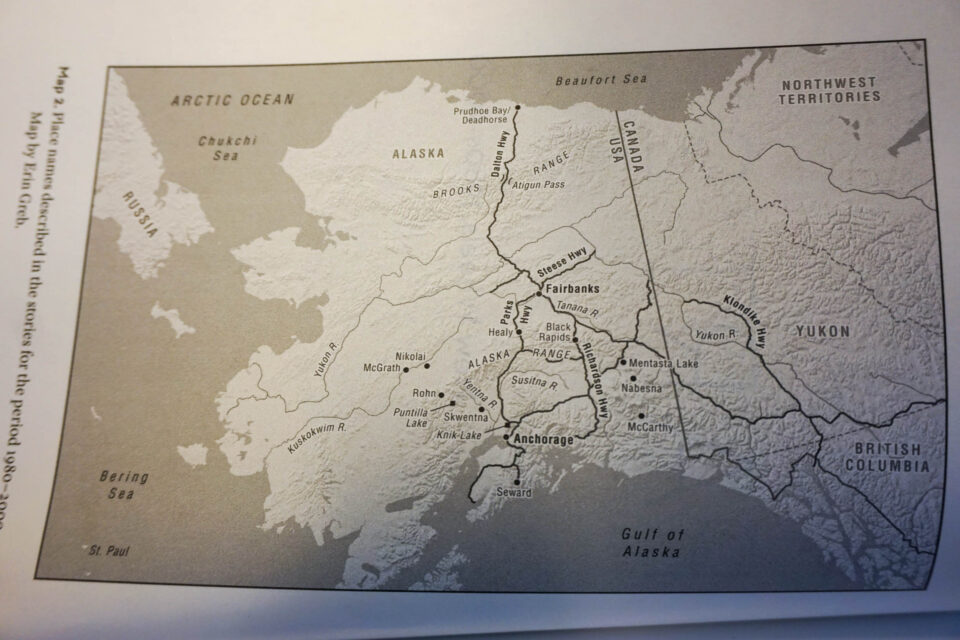

These journeys eventually carried me north; I’ve been in Alaska for over a decade now. I’ve bicycled long, mostly empty highways. I’ve dabbled in fat bike racing. Yet despite its reputation for wilderness adventure, I don’t ride up here as often as I’d like. Mostly, Alaska is just home. This northern landscape, sandwiched between Hawaii and Mexico on most maps, is where I fell in love, got married, and became a father. I can’t imagine living anywhere else.

In the challenging era of parenting small children, the circumstances of my life make big bicycle trips seem more like pipe dreams than possibilities. With the effort it takes just to go on a ride through the neighborhood, I find that more and more, I’ve become an armchair cyclist.

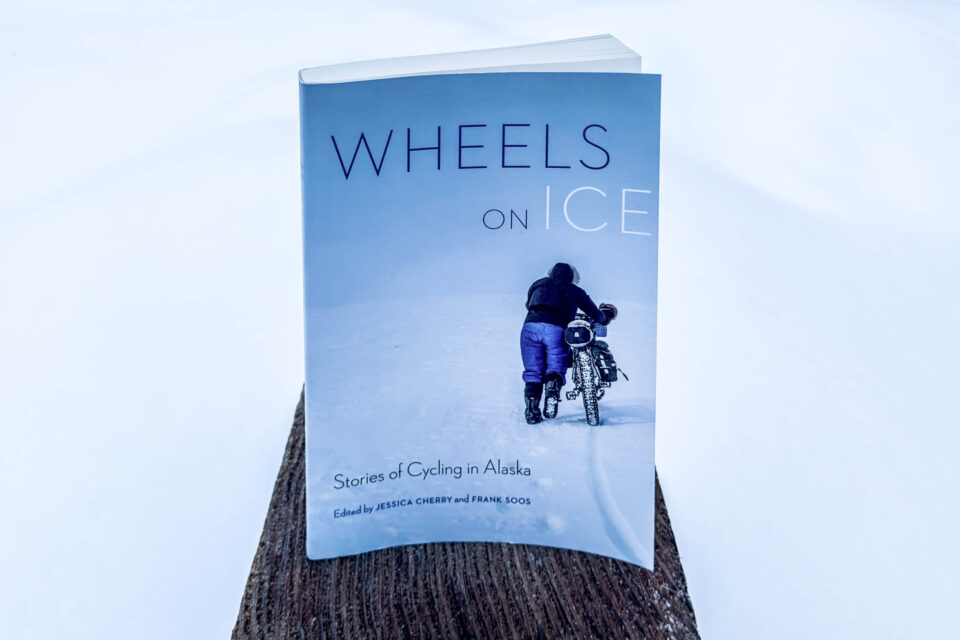

Enter Wheels on Ice: Stories of Cycling in Alaska. When I encountered this book, I was excited because, lately, reading stories about cycling offers a way of engaging with my favorite pastime that doesn’t require actually cycling. Besides, the collection featured some of my favorite writers (and riders), and it was all about Alaska. As I read it, though, I realized that Wheels on Ice does something far more powerful than the subtitle promises: it offers a means for redefining the North and gives me hope for a more rideable Northern future.

To understand how a book basically about riding bikes in the snow can transcend the niche of cycling stories, it’s important to know how the dominant narratives about a place come to define that place. In Alaska, the dominant narratives, historically and today, are about two things: adventure and extraction.

The narratives about resource exploitation—fish, gold, oil—claim that the opportunity to get rich is at our fingertips. Alaska is the “last frontier,” and nobody cares what you do, so take what you can and get out, because winter is coming. The depictions of icy expanses, northern lights, and dog mushing trails mostly exist as offshoots of that same frontier mentality. In the minds of Jon Krakauer acolytes, Alaska offers a blank canvas of empty wilderness where you can discover what you’re really made of.

Perceiving Alaska as either empty or exploitable creates a binary that ignores the fact that people actually live here. It ignores Indigenous realities. It ignores the complexity of history, politics, and land management. It doesn’t allow Alaska to just be a normal place with cities, families, and some folks who like to ride bikes.

Wheels on Ice connects Alaska’s history, people, and landscape to the act of cycling in ways that make riding seem both exotic and accessible. It gives a guy like me—who rides maybe a couple of times a month—a lot of hope. As editor Jessica Cherry writes, “Just riding your bike to work in America is an adventure, as much as it is an act of rebellion against our car culture. It is enough. Exploration, Polar or otherwise, is a frame of mind.”

Certainly, Wheels on Ice celebrates 40-below weather, feats of endurance, and remote wilderness—those things we usually associate with adventure in Alaska—but it also celebrates people just commuting to work. In refusing to limit contributions to only the wildest cycling efforts, we are invited to re-envision the way bicycles fit within those dominant narratives about the far North. At the core of this book lies a simple concept: whatever the terrain or weather, bicycling is about having fun.

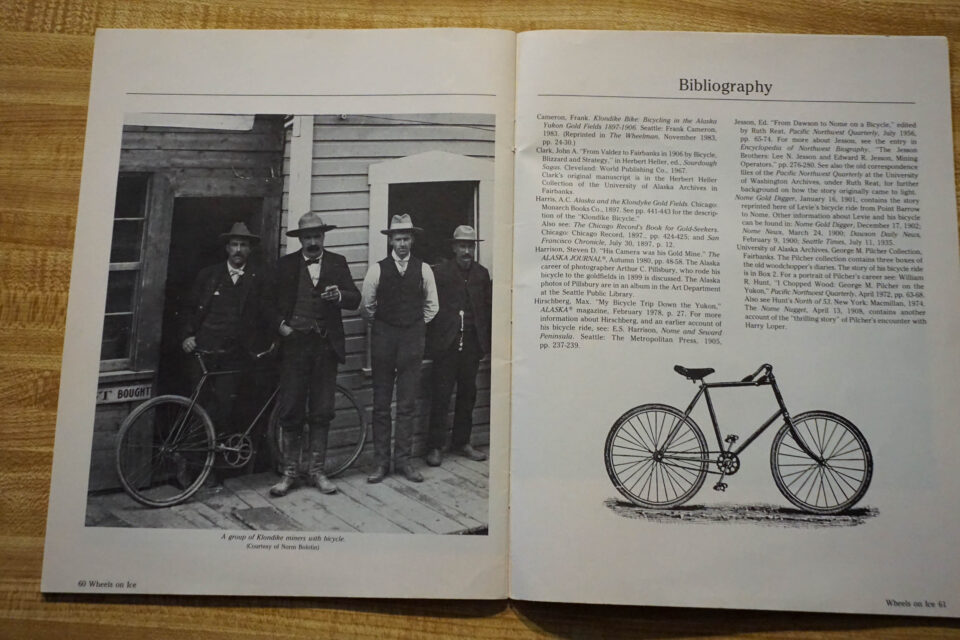

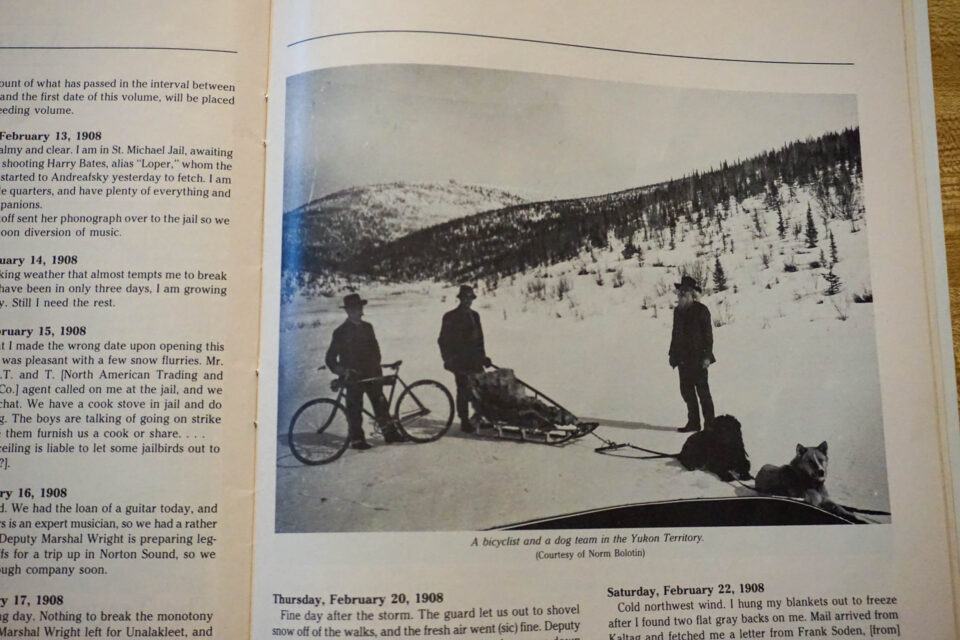

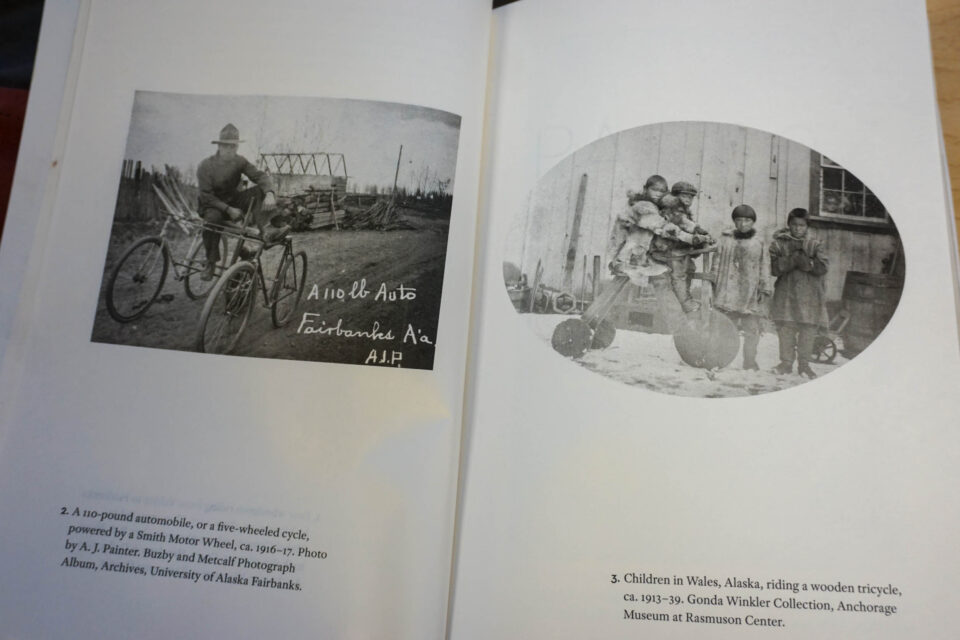

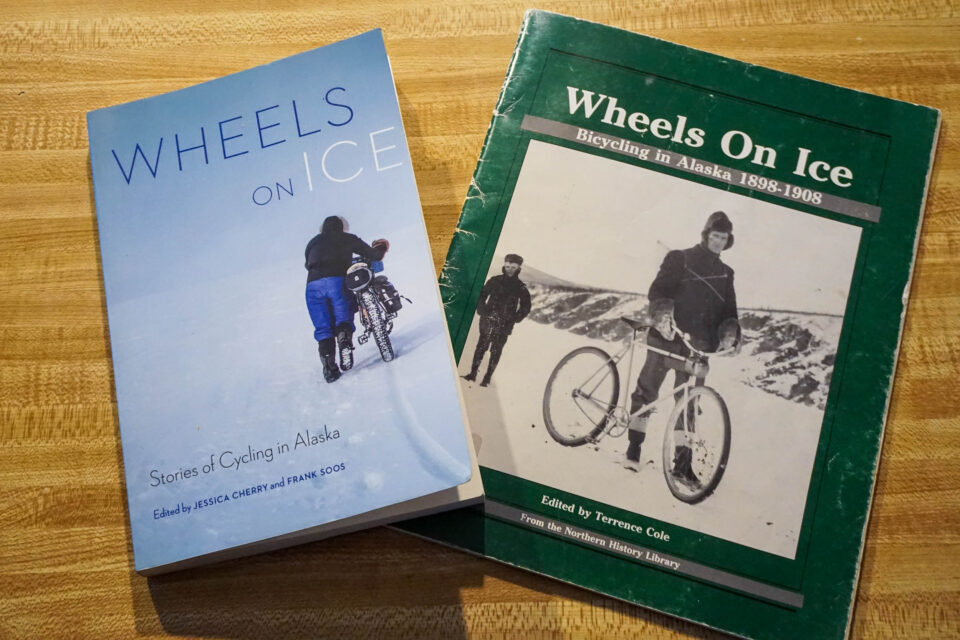

The idea for Wheels on Ice grew from an old pamphlet of the same title collected back in 1985 by Alaska historian Terrence Cole. An avid cyclist, Cole dredged up journal entries of “wheelmen” (who, then as now, were considered “a little mentally deranged”) pedaling down the Yukon River and compiled them into a 64-page volume. That original book, nearly impossible to find outside the special collections of local libraries, provided a new perspective on the Northern landscape (which, then as now, is viewed by outsiders as a frozen wasteland), one that portrayed bicycles as a unique and important part of the history of our state.

In 2019, Terrence Cole faced a terminal cancer diagnosis, and two of his colleagues at the University of Alaska Fairbanks decided that the original volume deserved reprinting. The resulting project took editors Frank Soos and Jessica Cherry two years and grew to include modern cycling accounts as well. They reached out to writers who bicycle and to cyclists who do things interesting enough to write about. Wheels on Ice grew from a tiny historical document to a book framed around three eras of major cultural shift in Alaska—the Gold Rush, the post-oil pipeline boom, and the near present.

While Soos and Cherry were still compiling the manuscript, Cole succumbed to his cancer. Then, when the book had been picked up for publication by University of Nebraska Press, Frank Soos was killed in a cycling accident while traveling in the Lower 48. The loss of two incredible thinkers and cyclists so connected to this book makes the anthology feel all the more powerful, both an elegy to the past and a promise for the future.

The greatly expanded Wheels on Ice provides a beautiful venue for Cole’s original historical pamphlet. Now, those historical accounts help us understand what a 2016 academic report from the UArctic Congress argues: that the bicycle can be a viable tool for fostering transportation resiliency in the face of climate change. In Alaska and across the circumpolar North, bicycling doesn’t have to be a fringe hobby.

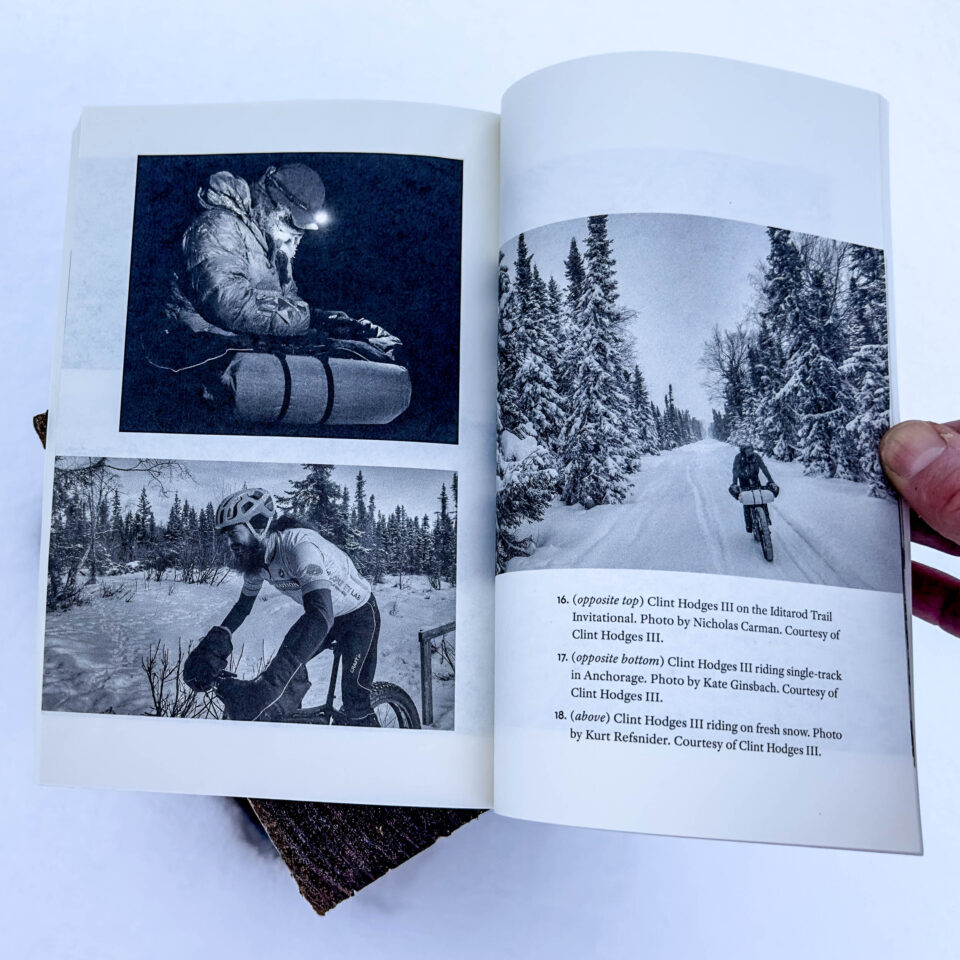

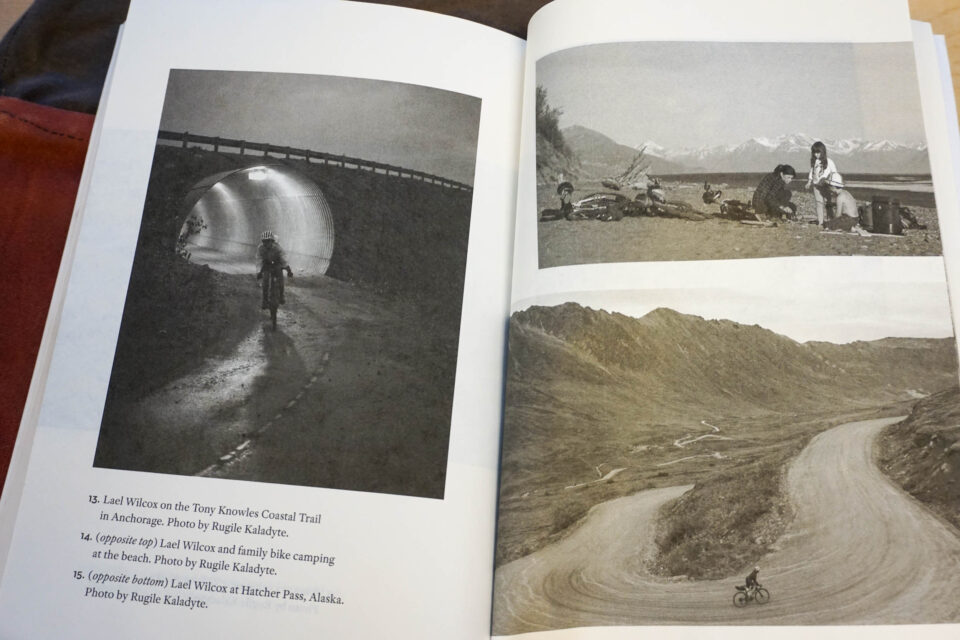

To be sure, all the famous badasses of Alaska cycling are here. Lael Wilcox rides every road in the state in the course of a few days. Bjorn Olson laughs at a hurricane somewhere along the coast of the Beaufort Sea. Roman Dial proves that while one cannot, in fact, bicycle through the rugged terrain of the Central Alaska Range, it is apparently possible to carry a bike across several glaciers and through miles upon miles of brush in search of sub-par descents.

We read about the early days of the Iditarod Trail Invitational when riders welded rims together and engaged in the kind of intrepid experimentation that would evolve into the modern-day fat bike craze. One story by Michael Finkel, originally an Atlantic article titled “Rough-Terrain Unicycling, 1997,” profiles a judge in Seward whose obsession with unicycles made him the world’s best single-wheel mountain cyclist.

However, bike history serves more as a backdrop for the writing on modern cycling accounts. We realize that Ed Jesson, who cycled from Dawson to Nome in the winter of 1898, didn’t travel through the terrifying wilds of cold and death depicted in Jack London’s stories. Cold, sure, but he pedaled a route where roadhouses provided ample food, warmth, and shelter for his entire journey.

By the end, Jesson’s ride down the Yukon doesn’t seem so incredible, and much of the book’s last section depicts cycling as simply part of daily life rather than a mere tool for adventure. “The frontier hasn’t so much closed as it has disappeared as a figment of the colonial imagination,” writes Cherry. “For many of us living here now, bicycling is not just our means of coping with modern life but our vision for a better, more inclusive, more sustainable future.”

Jeff Oatley sums up well the role of the bicycle in establishing that promised sustainable future in his account of a long winter journey. “When you’re along on the trail, battling everything from the weather to your own thoughts, it can feel dramatic… like you are really doing something,” he writes. But that, he argues, isn’t the point of riding. However big or small your journey, however you decide to do it, bicycling should be fun. No matter what, it’s “just a bike ride.”

When people are just out riding, the depiction of cycling in the far North feels most honest and important. M.C. Mahogani Magnetek, a Black transgender activist, undertakes a century ride through the streets of Anchorage in the rain to highlight the lack of mental health advocacy for trans people. Alys Culhane, age 64, overloads her old, poorly maintained touring bike and hits the highway to promote literacy and keep good books out of landfills. Don Rearden pays homage to an infamous bike thief from his hometown of Bethel.

Several writers discuss city riding. When Martha Amore, a year-round rider who “bears witness to urban Anchorage” on her morning commute, pauses at an intersection to converse with a group of unhoused residents, she demonstrates how a bike ride can connect us with our communities. In one of my favorite pieces, novelist Andromeda Romano-Lax attempts to bicycle up a hill—a seemingly small feat that leaves her winded. Her subsequent effort to improve mirrors her climb out of a deep funk and reminds us how important mental health is for Northern residents. Romano-Lax’s training also becomes a way to steal back essential leisure time from the onslaught of daily life. In other words, riding a bike can save us from both depression and capitalism.

The promising future for Alaska cycling often appears in subtle ways, as in David James’s ruminations on several decades of riding around Fairbanks, a place where “a quick trip to buy milk can turn into a mountain bike adventure.” Here, he observes that winter biking has changed the political dynamics between motorized and non-motorized trail users in Alaskan communities.

“Fat bikes haven’t just made my life better,” James writes. “They’ve been part of easing tensions in my community. A bike might have a human engine, but with all its interworking parts it’s still mechanical. Perhaps the bicycle itself provides the meeting ground between the two formerly warring camps.”

For me, this book provided an antidote to the trapped feelings that grow out of the overwhelming grind of balancing work, parenting, and winter. I needed to hear the kind of hope that Wheels on Ice provided, badly. I needed reminding that no matter how far-flung the journey or easy the commute, it’s always “just a bike ride.”

However often you ride bikes, you’ll find something beautiful in this 320-page collection. You’ll probably also find something inspiring. I certainly did, and when I finished reading, I pulled on my boots and went for a long ride.

Get a copy of this book here or order it through your local bookstore.

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.