Why Race? Reflections on the Tour Divide

Share This

As someone attracted to pedaling at an unhurried pace that allows time to soak in the surroundings and experience the local culture, Ty Domin was initially skeptical about racing the Tour Divide. Still, something compelled him to give a whirl. In this piece, explores the eye-opening experiences that helped him fully appreciate the iconic race’s allure. Read it here…

Words and photos by Ty Domin

I received some philosophical feedback from many BIKPEACKING.com readers after my last article on Overlanding. The discussion mostly revolved around the difference between racing and long-term touring and the fact that it’s not easy for some to mentally adapt from one to the other. To provide a more balanced perspective, I found myself sharing some writing I completed shortly after racing the Tour Divide in 2017, which was previously published in Cordillera Volume 9 in paperback. While it is specifically about the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) and Tour Divide (TD) race, it can no doubt be shaped around many other races and routes the world over. Find it below.

I was skeptical about taking part in the Tour Divide prior to my departure from Australia. My serious racing years are almost a decade behind me, and since then, I have spent years living on my bike, taking all the time needed to experience the world and its varying cultures. The self-supported bikepacking races I’ve taken part in have been approached with the cliché attitude of “touring with a sense of urgency.” Besides, one only needs to join the growing number of social media groups surrounding the event to begin to wonder how much of an underground and self-supported race it really is anymore. There’s constant internet support and connectivity, a plethora of pre-packaged resources created by huge numbers of participants over the years, the extremely well-trodden route, and the opinion that a huge number of those participants are returning riders with an immeasurable advantage over the “rookies.”

Has the Tour Divide’s time passed? It’s certainly no longer “the hardest race in the world.” So, why not avoid the Tour Divide and ride the GDMBR at my own pace, eight hours a day on the bike rather than 18?

I attempted the race for a few reasons, but primarily because TD veterans I knew and respected often possessed a dreamlike gaze—a hundred-yard stare—whenever it was mentioned. Soft-spoken cyclists became animated when talking about it, and when in a room together, they possessed a kindred bond. Bewilderingly, they all wanted to go back, a phenomenon that to me was unthinkable when there are so many other routes and races to undertake all over the world. I needed to know what it was about. With a month of leave at my disposal, the TD gave me intrigue, a start date, a pre-determined route, and what I thought would be more motivation to tour with a sense of urgency than a pre-booked flight home would.

Arriving at the YWCA in Banff, my fears of a less-than-underground atmosphere were brought to reality. If I were to generalise, there were three types of people inside the bell curve. Firstly, the serious racers, usually veterans, well prepared and focused on nothing but efficiency over the route. Then the “bucket-listers,” usually not highly experienced bikepackers, from North America, good-natured, and in possession of all the gear; infinitely comparing, adjusting, and talking about it while frantically undertaking last-minute tasks. And lastly, the confused foreigners, usually well experienced and in North America for a different experience from their home soil, a good position in the ranking at the end of the race being a bonus.

As such, for me, 8 a.m. on June 9, 2017, was a huge relief. All the background hype was meaningless once I was on the route; I deliberately pushed on, taking fewer photos than I may have wanted and forgoing extended breaks to separate from the bulk of the crowd. The challenges were regular that day, and by mid-afternoon, it felt as though we had been on the trail for far longer than the few hours that had passed since Crazy Larry sent us on our way. I chatted with other racers as they came and went due to the nature of the differing tempos between the geared riders and my singlespeed. As the field spread out and the obvious trappings of the race dissipated, the deep wilderness began to give way to more regular civilisation and interactions with locals, different cultures, and changing landscapes.

It was in the preceding days that I began to realise one of the reasons those veterans might keep on coming back. It dawned on me that the GDMBR really is the bikepacking version of the Great American Road Trip. It’s a long panning shot from the top of the USA to the bottom, the ultimate expression of freedom over 4,500 kilometres. No roadblocks, just the need for a place to rest your head every night before continuing the journey at sunrise. The magic of my experience was further amplified by the sense of changing seasons as I gradually travelled toward the equator, despite just over 19 days elapsing.

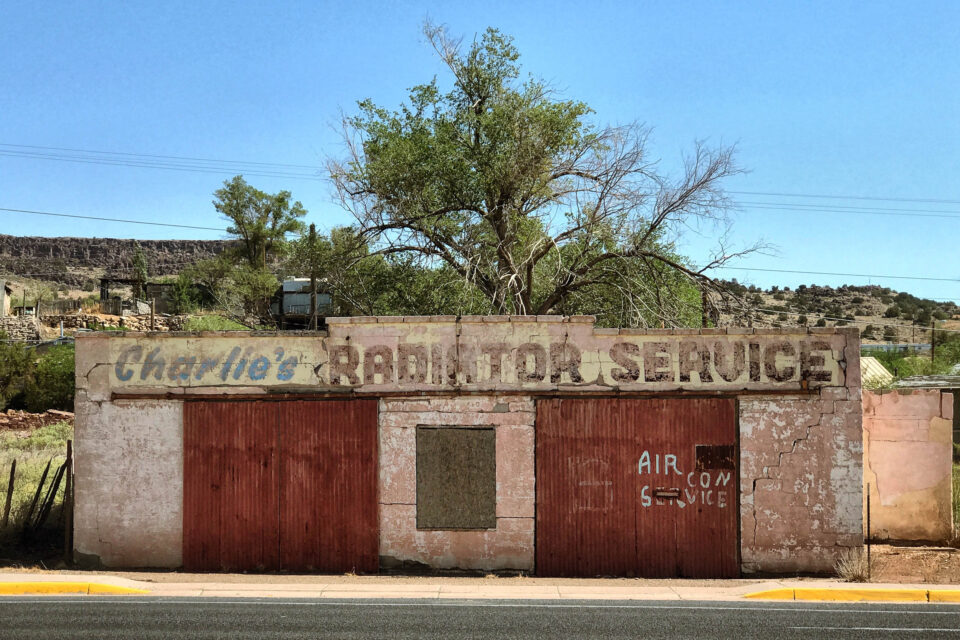

Daily geography changes meant I could experience different extremes of nature in a single rotation of the earth, waking up surrounded by snow and then rationing water that afternoon on a scorching desert plain. I was obsessed with the cultural changes I witnessed in those very same planetary rotations, and as I rode on, I often imagined the mystery and heartbreak that surrounded the abandoned towns and farmhouses on the route. I experienced the diversity of talking to a fourth-generation rancher one day, a tattooed barman serving a local IPA the next, and a Native American the day after. Outside of the race, time and distance were measured by change alone; the journey was always mysterious yet reassuring.

Despite recognising the value of experiencing as much as possible on the route, I didn’t question my choice to travel it at a race pace;. However, stopping for nothing more than supplies or a meal in a vibrant and history-rich town like Salida was hard for me when all I wanted to do was people-watch from the local pizza and brewhouse that had been recommended to me by Evan, a Northbound rider. As such, some mental anguish stemmed from the relentless nature of the race; watching the clock as I devoured several breakfasts at a diner wasn’t ideal when my usual travel regime was that of a touring cyclist, where three or four days of riding would be punctuated by at least one day off in an interesting town. As such, I’d go as far as to say that the Tour Divide wasn’t physically hard for me; it was just relentless, and my motivation only waned when I spied a magical campsite next to a stream, encountered a main street that deserved further exploration, or had to tear myself away from a conversation that could have continued into the night.

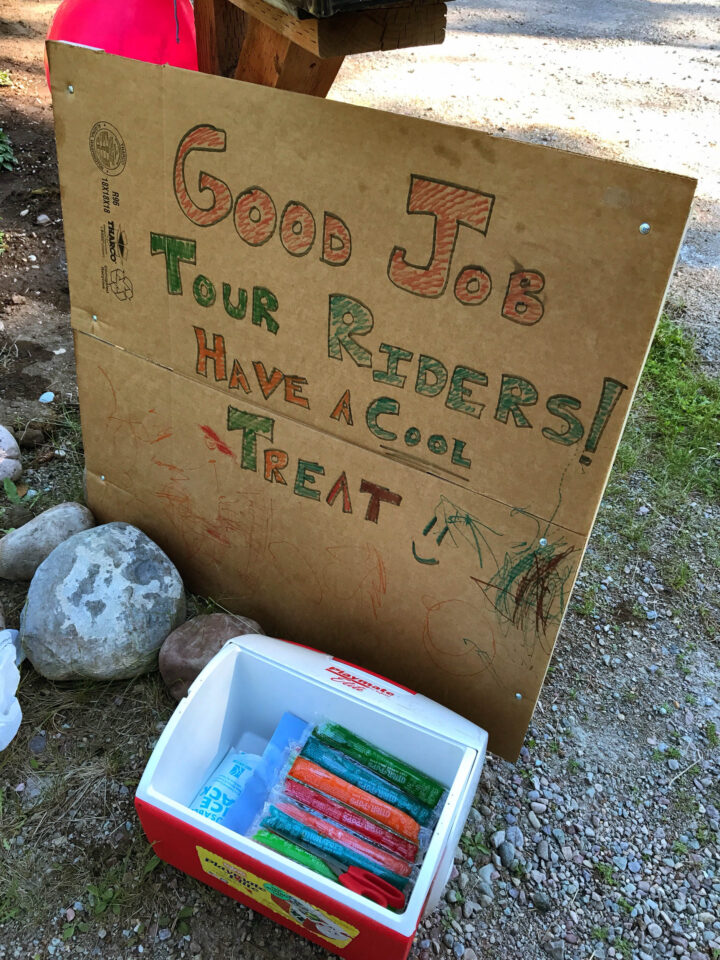

Aside from the undeniable sense of competition that all of us have to some extent (a sense I don’t like to admit but was obviously awoken on my last day when the prospect of finishing inside the top 10 was a reality), there are so many intangible benefits to taking part in the parade that is the Grand Depart. Nothing matches the feeling of arriving in a small town and having a local address you by your first name because they were tracking you online. There’s nothing like the monotonous voice in your head being replaced by that of another rider an hour into a seemingly endless hike-a-bike on a day when no one outside of the race would consider crossing that snowed-in pass.

There’s nothing like the laughter that ensues at a gas station when you exchange stories with a trucker who has just had a conversation with another exhausted and smelly racer up ahead. There’s nothing like the historical nature of following a path that legends like Mike Hall have suffered over, experiencing exactly what they have in bygone years. There’s nowhere else that friends, family, and strangers follow your movements online as part of a greater event and offer encouragement, connect with each other, and form a strong community. The race can even be the necessary evil that forces you to push your own limits when you could just as easily slip inside that cabin and hole up until the weather changes—not that there’s anything wrong with that.

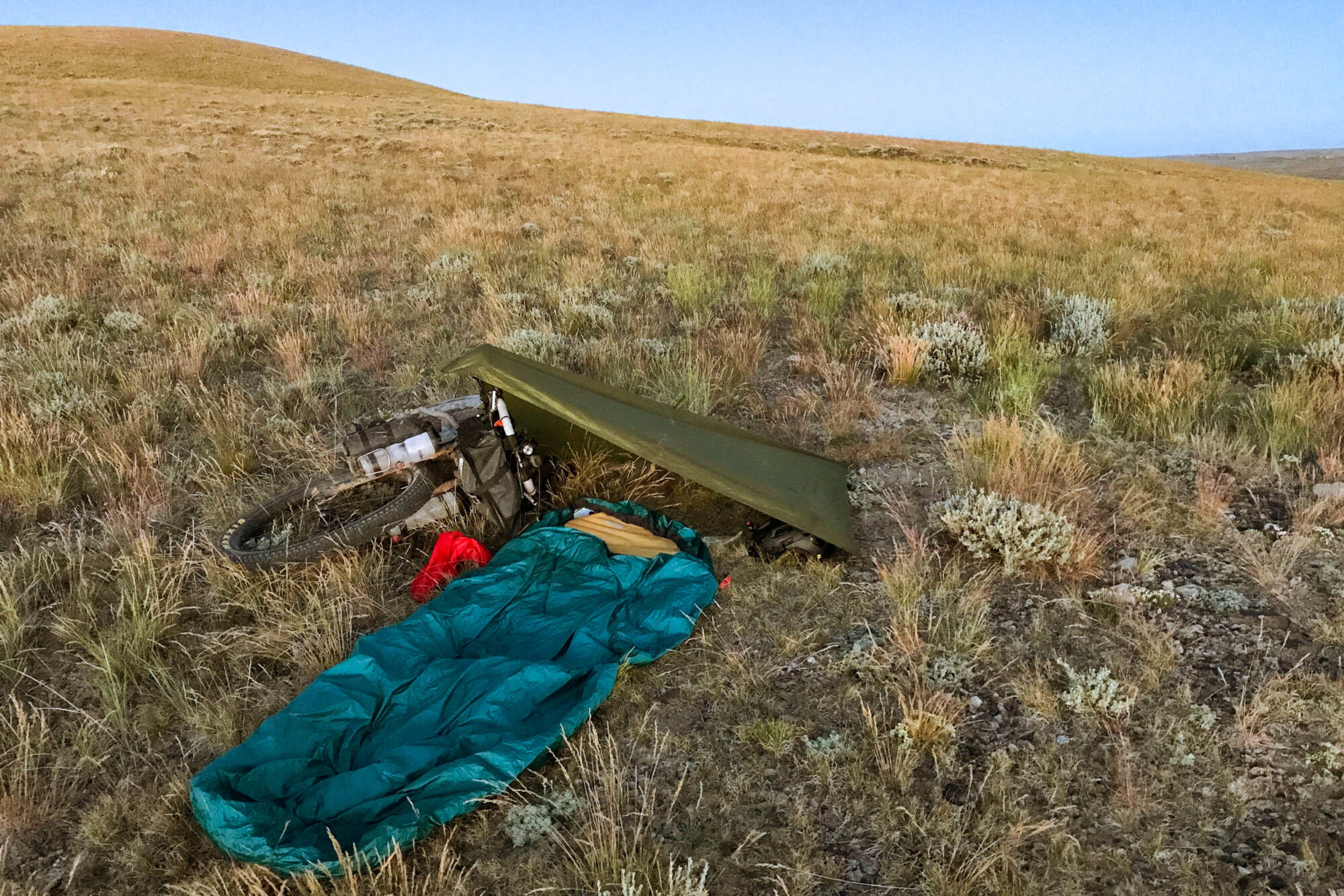

But above all, the race gives you an excuse to be that single-minded, aloof, and weathered cyclist who pushes beyond reason up unrideable inclines and into the night before scouring the countryside for a flat, out-of-sight piece of terrain on which to unroll a bivvy. It gives you an excuse to wake up the next day to do it all again on a diet of double and triple breakfasts and gas station junk food. It gives you an excuse to make no plans except to follow a line on a map until you reach an insignificant endpoint, forgetting where you even started that day.

Racing provides you an excuse to challenge yourself for no reason other than to reach new limits, be allocated a ranking against a pile of strangers, and perhaps earn the praise of a few dozen people on the planet. It gives you an excuse to leave regular life behind as a distant memory and an infrequent conversation with loved ones over the phone whenever there’s cell reception. Sure, you can do all this without the race being the backdrop, but then you’d have to make up an excuse whenever someone asked, “Why?”

So, what’s my point in sharing these thoughts? In short, my skepticism toward participating in the race was a waste of mental energy once I was out on the route and could appreciate the immensity of taking part in such an iconic event. I’m trying to portray the GDMBR as a marvel of geography and culture, which it never gets the appropriate credit for due to the constant overshadowing of the route as just a long mountain bike race. I’m trying to explain why someone who moved away from bike racing almost a decade ago and strongly identifies with a culture of casual touring and bikepacking might, after all, find something unique and ultimately valuable in taking part in the Tour Divide.

I have crossed well over 30 countries by bicycle, and I can’t recall a single long-distance route that I would repeat, mile for mile, anywhere else on the planet. The GDMBR, I would, and the race is icing on the cake. Or, as Mike Hall once described it, “A sporting bet struck between amateurs for the sheer sake of curiosity and an interesting life.”

Further Reading

Make sure to dig into these related articles for more info...

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.