Eastern Divide Trail (S1): Boreal

Distance

557 Mi.

(896 KM)Days

10

% Unpaved

94%

% Singletrack

0%

% Rideable (time)

100%

Total Ascent

16,573'

(5,051 M)High Point

1,567'

(478 M)Difficulty (1-10)

4?

- 2Climbing Scale Easy30 FT/MI (6 M/KM)

- 2Technical Difficulty Easy

- 4Physical Demand Fair

- 3Resupply & Logistics Fair

Contributed By

Logan Watts

Pedaling Nowhere

Words by John Duffett, Logan Watts, and Tsinnijinnie Russell / Photos by John Duffet

The 5,900-mile Eastern Divide Trail begins its multi-ecosystem traverse by crossing the island of Newfoundland, home to one of the southernmost large tracts of boreal forest in North America. Boreal forests—also known as taiga—are one of the world’s largest biomes, representing some 11% of Earth’s surface. Often considered the “lungs of the Earth,” these coniferous woodlands store and regulate carbon at massive scale, which is considered comparable to tropical rainforests. Today, the few small pockets of boreal forest in the United States are highly threatened by climate change.

The name of Segment 1 was inspired by these incredible forests and the etymology of the word itself. Latin Boreas means “north wind,” which is from Greek Boreas, the name of the god of the north wind. That’s more than fitting when considering the starting point of this monumental route is where the North Atlantic Ocean meets the Labrador Sea.

Beginning at the Cape Spear lighthouse—the oldest of its kind in the province—riders can stand with their back to the sea and know that the full extent of North America stretches out in front of their handlebars. Rolling westward, the route takes a short stint on pavement before connecting with the Newfoundland T’Railway, which Segment 1 follows almost in its entirety. But make no mistake, this isn’t your typical rail trail. The T’Railway climbs and descends far more than most, is made up of a variety of conditions and surfaces, and offers a good mix of rural, urban, and very remote settings. Better yet, it takes in some of Newfoundland’s most impressive landscapes, forests, Topsails, and rivers on its way to the terminus at Port Aux Basques.

Lay of the Land

By Tsinnijinnie Russell (@tsinbean)

Segment 1 of the Eastern Divide Trail is on the traditional lands of the Mi’kmaq Nation and Beothuk. The Beothuk were some of the original Indigenous inhabitants of the island now known as Newfoundland. They were a small tribe, with some estimates placing their numbers around 700-800 people at the time of first contact with European settlers. During the summers, they relied upon fisheries and fertile gathering areas along the coast for food and other resources. During the fall and winter months, the Beothuk withdrew inland to hunt caribou.

The Beothuk’s access to resources was dramatically impacted by permanent European settlements in the 17th century. Repeated hostilities and attacks from Europeans led the Beothuk to withdraw from trade and contact with European settlers. By 1829, the Beothuk no longer inhabited the island due to starvation, disease, and violence from European settlers. While some individuals may have integrated into other tribes such as the Mi’kmaq, most Beothuk and their culture were wiped out by European colonization.

Mi’kmaq oral tradition supports that Cape Breton and Newfoundland were both part of traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq. The island has been utilized by the Mi’kmaq as a hunting and fishing ground for thousands of years. In more recent centuries, the Mi’kmaq have set up more permanent settlements on the island. The Federation of Newfoundland Indians was formed in response to a 1972 decision to exclude the Mi’kmaq living in Newfoundland from the federal Indian Act. Today, the Federation has six affiliated Mi’kmaq bands living in Newfoundland.

The place names describes the Whereabouts tab were gathered from the Ktaqmkuk Handbook, a resource published by the Qalipu First Nation in 2018. The project is a culmination of over 20 years of research, utilizing a number of sources and researchers that included historians and linguists. The project shows that many of the locations were given literal names and often identified navigable routes, land and water, and food and resource areas. Some names, such as Gander Lake, seem to imply they were named post-colonization, or potentially renamed as a reaction to colonization. Other names are much older. The timeline provided by the Mi’kmaw Spirit website indicates that the Mi’kmaw inhabited the area for centuries prior to European colonization. The earliest identifiable petroglyphs are dated to 1200 CE, but the earliest signs of the Mi’kmaq in the region date back to 8400 BCE near Debert, Nova Scotia.

The Newfoundland Railway was constructed in the late 1800s, with the main line from St. John’s in the east to Port Aux Basques on the west coast completed in 1898. With few roads on the island at that time, the railway opened up Newfoundland’s interior to logging and mining and provided a link to some of the major coastal communities with branch lines. When the Trans-Canada Highway was completed across Newfoundland in 1965, the railway, which already operated at a loss, faced new competition. Passenger service ended in 1969, with freight service dwindling until the tracks were pulled up in 1988. The rail corridor is now a provincial park (known as the Newfoundland T’Railway), with conditions and usage varying widely across the province.

Route Difficulty

Physical Demand: 4 • Technical Challenge: 2 • Resupply/Logistics: 3

As a former railbed, the route’s grades are relatively low, the curves are gentle, and the trail is wide. As such, the only technical challenges are presented by the variety of surfaces. There are some short sections of deep sand (primarily along Grand Lake near Howley), long sections of loose railway ballast that are rutted by ATVs and crowded by alders, and some bumpy sections with large embedded rocks. There are also sections of fast-rolling hardpack and gravel road as well as smooth pea-gravel multi-use path (primarily near St. John’s). There are often puddles, which, whether you go through or around them, tend to slow the pace.

Although the grades are fairly gentle, you’ll still do around 600 to 1,000 meters of climbing per day. It is often windy in Newfoundland, and much of the terrain is fairly open. Hence, it is commonly recommended to travel the T’Railway from west to east with the prevailing wind, so riding from east to west may prove more difficult, depending on the conditions. There are options, though (see Must Know tab below). As the highway roughly parallels the route, there are many opportunities for resupply. All things considered, this is not a particularly challenging route; it’s just long. While there are significant sections that would be well suited to a gravel bike—like much of the EDT—a proper ATB or mountain bike is required, and plus tires would make it more pleasant (see Must Know tab for details).

Route Development

Thanks in large part to John Duffett, who wrote the route guide for the Newfoundland T’Railway. The EDT Segment 1 guide uses much of the information from it. As John put it, “I’m not sure who was the first to cycle the T’Railway as a bikepacking route, but the first time I’d heard of anyone riding it was in 2013 when a fellow named Malcolm posted a trip report on his blog. It remains an excellent resource for additional information on this route (as well as others in Newfoundland).” Based on our experience and feedback from other riders, the T’Railway is perfectly fitting for the ethos of the Eastern Divide Trail. However, we may consider alternative options in the future based on landmarks and terrain.

GPX download (link below) includes a detailed set of waypoints. Please keep personal copies set to private on RWGPS and other platforms. The Eastern Divide Trail was made possible by our Bikepacking Collective members. Consider joining to support the creation and free distribution of carefully planned and documented bikepacking routes like this one.

Submit Route Alert

As the leading creator and publisher of bikepacking routes, BIKEPACKING.com endeavors to maintain, improve, and advocate for our growing network of bikepacking routes all over the world. As such, our editorial team, route creators, and Route Stewards serve as mediators for route improvements and opportunities for connectivity, conservation, and community growth around these routes. To facilitate these efforts, we rely on our Bikepacking Collective and the greater bikepacking community to call attention to critical issues and opportunities that are discovered while riding these routes. If you have a vital issue or opportunity regarding this route that pertains to one of the subjects below, please let us know:

Highlights

Whereabouts

Must Know

Camping

Food/H2O

Trail Notes

- Starting at the easternmost point in North America at the historic Cape Spear lighthouse.

- Scenery – It’s hard to beat the views of the Long Range Mountains and the Codroy Valley on the west coast, but the high bogs punctuated by the Topsails are spectacular on a fine day too.

- Railway history – If the steel spikes that still litter the trail aren’t enough of a reminder, many towns along the trail still retain their railway stations or have rolling stock on display.

- Many of the original bridges and trestles are also still in place, including major spans at Stephenville Crossing and Bishop’s Falls, as well as a lift bridge near Howley.

- Passing through deep sections of boreal forest with large trees, bogs, and wildlife.

- The Main Dam just east of Deer Lake is a pretty impressive structure. It was built in the 1920s to supply power to the pulp and paper mill in Corner Brook.

- Berries! Blueberries are abundant on the barrens in August or September. Also, look for partridge berries (aka lingonberries) a little later in the fall.

Research and writing by Tsinnijinnie Russell (@tsinbean)

Place names were gathered from the Ktaqmuk Handbook, published in 2018 by the Qalipu First Nation. The Handbook is a great resource for learning the Indigenous place names of many geographic locations and landmarks. The handbook also has a pronunciation guide and the translations of the Mi’kmaq language. The handbook includes more information about the research process and also the Mi’kmaq names of even more locations in Newfoundland. Excerpt from Ktaqmkuk Handbook regarding naming:

“Throughout Mi’kma’ki (traditional Mi’kmaw lands) important landscape features served as physical maps to aid with all forms of navigation, and to assist with locating specific sources of food and other necessities. Typically, this form of traditional land-use mapping involved naming land and water features indicating where resources were to be found. By identifying and naming naturally-occurring and constructed features of the landscape appearing along the many routes, trails and traplines on the country, hunters, fishers and gatherers could readily navigate the land, and locate foods and other life-sustaining resources. As well as indicating locations, the names indicate a complex history of Mi’kmaw use and occupation of the lands and waterways on the island of Newfoundland. In some cases, the naming coincides with hunting, fishing and gathering; sometimes it reflects settlement – a relatively new form of use and occupation. In other cases, names indicate prominent and important landscape and water features.”

pinMile 9 (KM 14)

St. John’s

European colonizers began fur trapping in Newfoundland in the 17th century in Placentia and worked their way across the island. Over the course of 250 years, as Europeans moved further inland, the Beothuk were cut off from their vital resource, the sea, which led to starvation and death. Diseases such as smallpox and especially tuberculosis ravaged the population after more permanent European settlement in the 18th century. White settlers also considered them to be sub-human and dangerous, and they persecuted and murdered many of them. The Beothuk proudly resisted white colonization by denying missionaries and by refusing to integrate with the colonizers’ society. Shanawdithit, commonly believed to be the last known Beothuk, died in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in 1829. This cycling journey begins where Shanawdithit passed away in servitude; this should serve as a reminder that every pedal stroke along the Eastern Divide Trail pushes you across unceded Indigenous land. Much of the historical markers you’ll ride past fail to acknowledge huge parts of the history of the area.

pinMile 9 (KM 14)

Impact of Railways on Mi’kmaq

The construction of the railway in the 1890s greatly impacted the Mi’kmaq living in Newfoundland. The railway was intentionally designed to “modernize” the island by making the European settlements less dependent upon fisheries and diversifying the resources available for extraction by moving inward. Hunters coming inland on the railway decimated the caribou population, nearly causing the species to go extinct. The logging industry that grew alongside the railway became increasingly destructive, and the Mi’kmaq became dependent upon the logging industry to earn wages to buy food and other supplies they previously were able to gain through hunting, fishing, and trading furs.

pinMile 215 (KM 346)

Gander Lake

Gander Lake is the third largest lake in the Newfoundland and Labrador province of Canada. This lake is the main source of water for the towns of Gander, Appleton, and Glenwood, all of which are located on the shores of the lake. The Mi’kmaq name of the lake is Akilasie’wa’kik Qospem (pronounced AH-GLASS-EH-EW-WHA-GEK HUSBEM) and the translation is descriptive for “lake at place of the english”.

pinMile 285 (KM 458)

Grand Falls-Windsor

This town is the largest town in the central region of Newfoundland. The towns close proximity to the Newfoundland Railway helped it grow, as well as the town’s proximity to extractive industries such as lumber and hydro-electric power. The English name for the town comes from Lieutenant John Cartwright, who named a waterfall he found in the area Grand Falls. The Mi’kmaq name for the town is Qapskw (pronounced HAP-SKOOK), which translates to “water fall (plural)”. This is also the same name the Mi’kmaq use for Victoria Lake Falls.

pinMile 302 (KM 486)

Exploits River

Running through the Exploits Valley, the Exploits River is the longest river on the island coming in at 246 kilometers (152 miles) in length. The river drains Red Indian Lake and deposits into the Bay of Exploits. Atlantic salmon use the river as a spawning ground and fish ladders have been installed in order to help increase the salmon population. The Mi’kmaq name for the river is Sple’tk (pronounced SPLAY-TE-KE) and is also called Tenenigeg.

pinMile 368 (KM 592)

Grand Lake

Covering an area of 543km2 (210 sq miles), Grand Lake is the largest lake on Newfoundland. In 1924, flooding from the Main Dam on Junction Brook caused Grand Lake to combine with Sandy Lake and Birchy Lake. The Mi’kmaq name for the lake is Wli’Qospem (pronounced WOLLY-HUS-BEM), which translates to “great lake”. The lake drains into Deer Lake through the Humber Canal and then into the Bay of Islands via the Humber River.

pinMile 373 (KM 600)

Impact of Hydroelectricity on Indigenous populations

The construction of various dams—such as the Grand Dam—and hydroelectric plants changed the landscape by flooding caribou habitat. Flooding the landscape destroyed the Mi’kmaq’s ability to harvest this traditional food source. The construction of power transmission lines also cut through trapping lines, travel paths, and hunting grounds.

pinMile 383 (KM 616)

Deer Lake

This lake is located on the western half of Newfoundland. The town of Deer Lake, unsurprisingly, derives its name from this body of water. The English settlers who arrived in the Humber River Valley named the lake after the Caribou who inhabited the area, who they referred to as deer. The Mi’kmaq name for the lake is Qalipue’katik. This name is derived from the word Qalipu, the Mi’kmaq word for Caribou.

pinMile 440 (KM 708)

Annieopsquotch Mountains

The Annieopsquotch Mountains are located east of Bay St. George in the southwestern interior of Newfoundland. The range runs north-eastward between Victoria Lake and Red Indian Lake. The Mi’kmaq name for the range is Aniapskwoj (pronounced ANN-NEE-UP-SKWATCH), and the literal translation means “terrible rocks”. The highest peak sits at 687 meters (2,254 feet) above sea level.

pinMile 467 (KM 751)

Long Range Mountains

The Long Range Mountains are a beautiful range along the west coast of Newfoundland that forms the northernmost chain the Appalachians. The Mi’kmaq name of this place is Mekapisk (pronounced MEGA-BISK), which has a literal translation, meaning “bare and rocky mountains.” In 2003 it was announced that the International Appalachian Trail would be extended through the Long Range Mountains.

pinMile 556 (KM 895)

Port-aux-Basques

This town is located at the southernmost point of Newfoundland. The area was colonized in the early 1700s, making it the oldest collection of European settlements on the island. The Mi’kmaq name for the town is Sinalk, which means “to empty of water”.

When to go

- While this route is technically rideable from late spring to late fall, the best chances for good weather would be mid-July to mid-September, and for best trail conditions and minimum bugs, mid-August to mid-September.

- The weather in Newfoundland can be quite variable. Even in summer, you should be prepared for around 5°C (41°F) temps with high winds and rain. Starting in September, you may experience the tail end of hurricanes and tropical storms bringing gusty wind and precipitation.

Logistics

- Directions: The Eastern Divide Trail is oriented from north to south, starting at Cape Spear on the easternmost point of Newfoundland and North America and ending in Key West, Florida. However, we expect some folks will ride it from south to north. Each has its own set of benefits and challenges. One such example is right at the beginning of segment 1. Much of Newfoundland is fairly open and it can be windy. Hence, it is commonly recommended to travel west to east with the prevailing wind, but if you’re riding the Eastern Divide Trail from north to south, it seems only fitting to ride segment 1 from Cape Spear. However, unless you’re riding the route as an Individual Time Trial or record attempt, there’s no reason why you couldn’t ride from west to east, then ferry back to Sydney, Nova Scotia, from Argentia (near St. John’s) to continue your north-south trajectory.

- Getting there by land: Marine Atlantic provides ferry service from the mainland in Sydney, Nova Scotia, to Port Aux Basques year-round, and seasonally to Argentia, which is the one you want if riding the EDT from north to south. The price of the ferry at the time of publication is about $120, including all taxes and fees. From the ferry terminal at Argentia, you’d need to pedal or get transport to St. John’s to reach the beginning of the route. If getting there by bike, it will be a 145-kilometer (90-mile) ride using this spur of the T-railway and a little bit of pavement to connect with the main route. Or you can ride that same route to the Circle K at Whitbourne Jct and get on a DRL bus to St. John’s. On the current schedule, they depart at 8:15 p.m. local time. They allow bikes with a $35 surcharge, according to their website.

- Getting there by air: There are airports in Deer Lake, Gander, and St. John’s. The St. John’s International Airport (YYT) is the most convenient, being only 19 kilometers (12 miles) from the start of the route at Cape Spear. Additionally, it’s the largest airport and has regular service to and from Montreal and Toronto.

- Additional information on the Newfoundland T’Railway can be found on the Newfoundland/Labrador Parks website, the official T’Railway site, and our route guide.

Dangers and Annoyances

- Animals: There are black bears on most of the island, but none on the Avalon Peninsula, the southwest corner of the province. Other than black bears, there really aren’t any dangerous animals.

- Traffic: While the T’Railway is generally traffic-free, it is used by ATV traffic in some areas, plus cars and trucks for cabin access in specific places.

- Route finding: Navigation is generally easy, but there’s not much signage. The biggest navigational challenges are typically newly developed areas in “major” urban centers where roads and shopping centers have been built over the original railway alignment. The route shown addresses these, but is subject to change.

What Bike?

- The best bike for the entire Eastern Divide Trail is an ATB or Tour Divide-style bike. For drop-bar aficionados, the Salsa Fargo and Cutthroat come to mind, or the Surly Ghost Grappler or Tumbleweed Stargazer. For those who prefer flat bars, any moderate hardtail or rigid 29er would be great, such as the Surly Ogre or Bridge Club, Salsa Timberjack, or Otso Fenrir. That said, plus tires might be welcomed in some of the chunkier or loose sections of this segment.

- As for tires, we like fast-rolling XC rubber for this ride. Tires that folks like for the Tour Divide work well. The Maxxis Ikon, Teravail Ehline, and Vittoria Mezcal are all tires we’ve used while scouting.

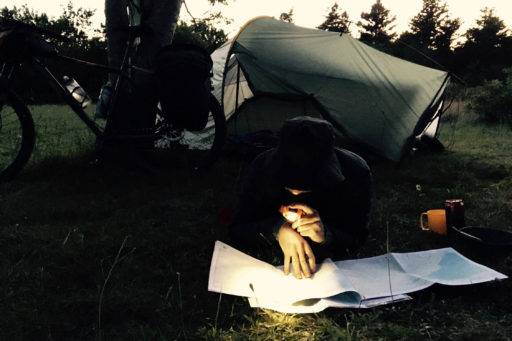

- Convenient public and private campgrounds as well as a few other good camp spots and lodging options are shown on the route map.

- In general, there are plenty of places to camp along the trail, which is mostly Crown Land. According to officials, you can camp anywhere along the route, except within other provincial parks that have conflicting rules. There are plenty of places to pitch a tent along the T’Railway, particularly in more remote areas.

- Locals can also give you good tips on places to camp, but beware that they may have a different idea of how far out of the way something is relative to someone traveling by bike!

- Campfires are not allowed on the T’Railway.

- There are hotels and motels in St. Johns, Clarenville, Gander, Grand Falls-Windsor, Deer Lake, Massey Drive, and Port Aux-Basque, and other lodges, and rental cabins can be found in other places.

- Water is generally not an issue. There are ample water sources along the trail if you plan on filtering or treating.

- Major centers such as Corner Brook, Deer Lake, Grand Falls, Gander, and Clarenville will have pretty much supplies you could need, and the trail passes right through each of them.

- Smaller towns will often have a convenience store or a gas station with at least some selection of food (and beer), and most days you’ll pass through at least a couple.

- The craft beer revolution was slow in coming to Newfoundland, but there are now breweries popping up all over – see map.

- The most remote sections are the Topsails (where you’ll find no services for about 100 kilometers between Badger and Howley), and the Isthmus (there isn’t much directly on the route for about 80 kilometers between Whitbourne and Goobies).

Here’s an example itinerary based on ~70-mile days. Some riders might prefer shorter days and others might average longer distances, but this is a solid baseline that a thru-rider might consider for a reasonable bikepacking itinerary. Note that this assumes you’re a fairly fast and seasoned rider carrying a medium-light load. Unless otherwise noted, camping is based on wild camping or nearby campgrounds/lodging.

locationCape Spear-Brigus Junction

Day 1 (84 KM +792 M / 52 MI +2,600 FT)

The route starts with a 12-kilometer stretch of pavement before joining the T’railway just south of St. John’s. From there, there are plenty of shops and restaurants for the next few miles through Mount Pearl. From there you continue on to the coast and then ride along the bay for 15km along a coastal section. From there you’ll head inland toward Whitmore. Once at Brigus Junction, you can go off route north to Gushue’s Pond Park or camp on the trail further on.

locationBrigus Junction-Goobies

Day 2 (113 KM +732 M / 70 MI +2,400 FT)

locationGoobies-Maccles Lake

Day 3 (106 KM +732 M / 66 MI +2,400 FT)

locationMaccles Lake-Notre Dame Provincial Park

Day 4 (109 KM +549 M / 68 MI +1,800 FT)

locationNotre Dame Provincial Park-Skull Pond

Day 5 (109 KM +610 M / 68 MI +2,000 FT)

locationSkull Pond-Deer Lake

Day 6 (116 KM +533 M / 72 MI +1,750 FT)

locationDeer Lake-Black Duck

Day 7 (121 KM +762 M / 75 MI +2,500 FT)

locationBlack Duck-Doyles

Day 8 (121 KM +762 M / 75 MI +2,500 FT)

locationDoyles-Port Aux Basques

Day 9 (40 KM +183 M / 25 MI +600 FT)

Riding the Eastern Divide Trail Segment 1 and the main line of the T’Railway from St. John’s to Port Aux Basques is a long enough trip on its own, however for those looking for additional adventure, there are a plethora of options to consider. The mainline doesn’t provide a lot of the typical Newfoundland tourist experiences, so if you’ve never been, it may be worth considering some offshoots if you want to spend more time there, or otherwise extend your trip for some sightseeing. For more information on options, check out the Trail Notes section under the Newfoundland T’Railway guide here.

Terms of Use: As with each bikepacking route guide published on BIKEPACKING.com, should you choose to cycle this route, do so at your own risk. Prior to setting out check current local weather, conditions, and land/road closures. While riding, obey all public and private land use restrictions and rules, carry proper safety and navigational equipment, and of course, follow the #leavenotrace guidelines. The information found herein is simply a planning resource to be used as a point of inspiration in conjunction with your own due-diligence. In spite of the fact that this route, associated GPS track (GPX and maps), and all route guidelines were prepared under diligent research by the specified contributor and/or contributors, the accuracy of such and judgement of the author is not guaranteed. BIKEPACKING.com LLC, its partners, associates, and contributors are in no way liable for personal injury, damage to personal property, or any other such situation that might happen to individual riders cycling or following this route.

Please keep the conversation civil, constructive, and inclusive, or your comment will be removed.