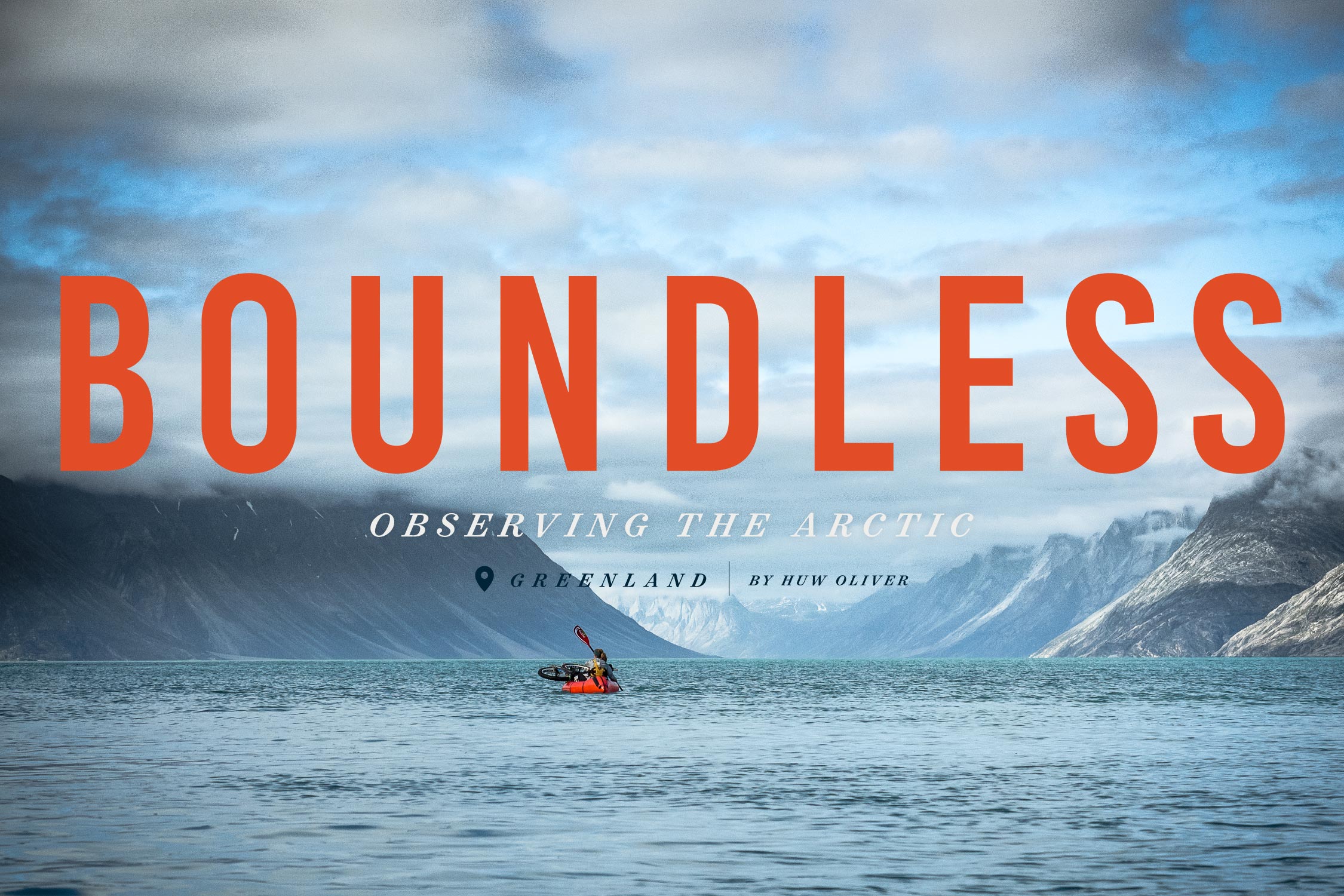

Boundless

In this feature story, originally shared in the first issue of our printed publication, The Bikepacking Journal, Huw Oliver and Annie Le pedal and paddle their way across Greenland, traversing the country’s immense landscapes and isolated fjords. They observe and appreciate the wild and barren terrain as they make their way through it, celebrating every sign of life and earning each mile that ticks by…

This story originally appeared in the first issue of The Bikepacking Journal, our biannually printed publication, in October 2018. To read more stories like this one – in the full glory of print – consider joining our Bikepacking Collective. We need your support. By doing so, you’ll receive two beautiful journals packed with the best bikepacking stories and photography from around the world delivered to your doorstep each year.

Three parallel tracks led straight on, seeming to merge as they crested the next dune. The two tracks on the right were pairs of reniform depressions like cupped hands in the sand, one set a miniature version of the other. On the left, the smaller, uniformly square-edged indentations left by rolling rubber mirrored the direction of the two muskoxen up the valley. I followed, adding my own track to the others, weaving around the huge blocks of striated granite peppering the sand. As I rode, my field of view constantly shifted around these obstacles and the domed dunes, until I spotted a stationary Annie and, simultaneously, her reason for stopping. She turned to meet my eye but said nothing.

A muskox cow and her calf, the source of the tracks we had been following, became visible as suddenly as if they had sprung up out of the ground. I stopped, and for a moment all four of us were held in a stillness laden with tension. From 25 metres away I could see the subtle shades of brown and cream shimmering within their long coats and the lightening of the mother’s recurved horns as they narrowed to points, and I could smell the tang of oily wool. Perhaps it was the quality of the afternoon light reflecting from the glacier, or the fact that she was so fiercely alive amid inert sand and rock, but she had a captivating clarity. While I fixed my eyes on hers, watching for signs of what would happen next, my fingers moved of their own accord towards the camera still hanging from my neck. I managed to rattle off a couple of frames just as she lowered her horns towards the ground, her disgruntled snuffle indicating that she wasn’t as happy as we were about the surprise meeting. With a snort and the clatter of hooves on pebbles, cow and calf were off in the opposite direction. The adult’s ungainly gallop made her floor-length fringe of wool swish and sway, looking like a colossal toupee sashaying across the sand.

After a few minutes’ head start, we followed them. With the fjord now behind us, 1,000 metres of granite on the left, and the violence of a glacial river to the right, our journey lay ahead. Several kilometres of dunes awaited us, interspersed with boulders and sparse clumps of marram grass. This was Greenland, not that you would have guessed it.

The day before, we had deflated our packrafts and loaded them back onto our bikes, the first leg of our journey down Kangerlussuaq Fjord complete. The slide into expedition life is always a welcome one, allowing our modern, self-imposed timetables to fall from us like a shed skin. During the flat-water journey from the head of the fjord to this desert valley, we were beholden to the wind and the tide. We navigated our unlikely flotilla of bike-laden boats between the walls of the fjord, stopping when the tide turned from ebb back to flood, often paddling late into the Arctic night when the wind and tide allowed. From the start, we had no choice but to listen to the land and the water if we were to travel through it.

I had never before perceived a landscape so defined by its light. It filled the air, unalloyed, from when we woke until we slept, and seemed to come from every point at once, reflected by water, rock, and ice. It posed its own challenges: our brains were used to the increasingly blue light reflected by distant objects, but with so little to impede its progress the light could travel further without change. For five days we paddled on, watching the same pointed peak on the horizon detach itself almost imperceptibly from the others, stepping forward from the backdrop to become a moveable landmark level with our destination. When we needed to cross the fjord, our eyes insisted that the distance was only a kilometer or so, but we had to look repeatedly at the map to remind ourselves that it was actually five. It was a committing section of mercurial waterscape that repeatedly transformed from millpond flat to capriciously rough. While paddling, the light shone particularly bright from a point above the horizon, where the two sides merged and our view of the water ended. It was ice blink – the glare of an unseen ice field reflected onto the underside of the clouds.

Now among the dunes, we stood in the rain shadow of that ice, a smaller fragment of Greenland’s main ice sheet, whose height and bulk waylaid the precipitation coming off the sea from the Davis Strait before it could reach us. It was an Arctic desert, stretching straight inland along the path once taken by flowing ice, walled in by granite, and floored by the accumulated dust and sand of pulverized mountains. The wind sheeted down from the ice above, whipping the dust into violent fits around us. The inner scaffolding of the earth was still plain to see, stripped clear by the passing of ice. Moraines 100 metres high were dwarfed by rock walls that revealed layers as old as almost anywhere on earth.

Life was there, just as we were, though it had a self-evident tenuousness in the ankle-high forests of dwarf birch and in the relatively few species of animal that make their home above the Arctic Circle. The pinpricks of life across the valley were like stars against a black sky, but like stars they burned brightly. The white coat of a hare that sat up to eye us as we approached, the hot pink flowers of fireweed that flashed among the gravel banks beside the ominously dark water of the river. Everything here depended on light from a sun that was omnipresent during the summer and absent during the long dead of winter. A bed of flowers blossomed from the desiccated carcass of a muskox. Here, life was always shadowed by death.

We learned to read the well-worn trails of the muskoxen and occasional caribou whose meandering routes across moraines and around river bends reflected older knowledge than our own. The trails led from terminal moraines that barred us from the fjord where we started, following the river that ricocheted from one side of the valley to the other, which forced an unwelcome hike-a-bike across sloping rock terraces laden with scree, perched above the roaring alluvial soup below. They ran faintly across the blasted outwash plains, pancake flat and broken only by frequent, ageless skeletons. They split, rejoined, and passed the enduring signs of past human presence in the valley: a ring of stones where a hunter once set out his tent, or a bone midden emerging from an eroded bank.

Eventually, water blocked the way, but this time it had depth. We had passed a split in the valley, and while the opaque glacial waters continued to the southeast, the northeast branch flowed clear. Though not more than five metres wide, the water was deep, and it was worth the time to inflate the boats again and paddle across. On the far side, the land emerged more vibrant with life where marshes pooled between moraines. Small groups of muskoxen milled about in their characteristic way, one or two at first, but then dozens once we looked more closely for them, nibbling away beside the water above billowing wheatgrass-coloured fronds. The muskoxen were as pervasive a presence as the continual rumble of our tyres over the ascetic landscape and would look up as we approached, seeming to gauge our arrival as if we were guests on their threshold, before going back to contented grazing.

If they were unlikely inhabitants of the valley, then we might as well have landed in a spaceship. The humble bicycle can take you as far as you can dream, and I can think of some unexpectedly wonderful places in which I’ve turned a pedal before, but riding through this valley bordered on surreal. It’s liberating to leave the confines of a trail, letting the mind wonder as the tyres wander. A smile tugs at your mouth and you feel as if you could go… anywhere. There was no defined path, and so we chose constantly between this game trail and that one, between one side of a moraine and another, until we each rode our own separate, personal paths. Sometimes we would ride side by side, and Annie might point out a flower, or a curious arrangement of stones that we imagined was all that remained of a long-abandoned hunter’s camp. Other times we would separate, content in our own conversations with the place.

The riding was precarious. Having to push – sometimes for a minute and other times for half a day – was all part of the game. The boating, too, required conditions that were just right. Forget trying to paddle against a strong tidal flow. And the wind forced us to seek shelter on a rock shelf for a few hours whenever it picked up. Both modes of travel proved unpredictable in a region of undeveloped terrain and powerful natural forces. Paddling and cycling need the right conditions to flourish, just like the animal populations in the Arctic whose food supply is subject to the severity of the winter. But there is joy in that delicate balance. A fatbike and a packraft ask for nothing but creativity and determination – they are simple and boundless, the modern cousins of the dogsled and qajaq that Greenlanders have used to traverse land and water for centuries.

The trails wound on, marked periodically with reassuring scraps of muskox wool caught on a branch or rock, confirmation that our guides had recently passed this way. The landscape was always the same, always different: a series of vignettes played out for no one in particular. A char swam lazily upstream over gravel banks beside us as we pedaled, given away by light that fell uninterrupted through the glassy water and onto the titanium silver of its back. A fox emerged from the willows, leaving the cover of the trees to continue its ceaseless trot across the land. It would stop often, sniff the air, and then set off on a tangent, its sharp eyes framed by a summer coat the matte brown of coffee beans. A pair of white-tailed eagles spread massive wings and circled us noisily, screeching indignation as we passed beneath the crag on which they must have made their nest. We fell in love with the land.

A fatbike and a packraft ask for nothing but creativity and determination – they are simple and boundless, the modern cousins of the dogsled and qajaq that Greenlanders have used to traverse land and water for centuries.

It would be hard to find a better champion of the Arctic than Barry Lopez in his classic book Arctic Dreams, his love song to, and exploration of, the Arctic’s presence both physically and in our consciousness. He recalls asking an Inuit man what he does when he enters a new landscape. “I listen,” he replies. Lopez wonders whether a landscape can be understood at all, or whether it is better approached without expectation if “one simply accords them the standing that one grants the other mysteries, as distinguished from the puzzles, of life.” Unconsciously, that was what we did.

Sometimes, an adventure on your bike is an opportunity for introspection. The rhythm of the movement and of the days, and the focusing of the mind on the practicalities of the task, clears the path towards insight. In this instance we looked outwards rather than inwards – we might not have understood the land, but it acquired meaning. It had a presence that made us feel as though we could see everywhere and hear everything all at once, from the moan of the wind rushing up the valley at night to the tiny blueberries that slowly appeared as we hunted in the carpet of leaves.

Bicycle journeys have a tendency to draw people towards wide spaces and harsh environments, the places where life shines brightest. On a bike, whether you’re on the tarmac or bumbling across the tundra, you move at the pace of the land: fast enough to appreciate it changing around you, slow enough to marvel at the detail of a flower as it opens in the morning sun. Perhaps that willingness to go and dive in to a landscape, to accept it on its own terms rather than seeking to change or exploit it, is what ties together folks who make journeys by bike.

After a sharp bend in the river, the valley walls came together, and the scene resembled one of the many upland rivers back home in Scotland. The crowd of muskoxen through which we passed began to thin as we neared the edge of their protected area, although they still felt like companions as we pushed between patches of better trail. The ice was still present at the edge of vision, but as we paused beside a waterfall and its deep pool, rounded cushions of emerald moss springing from the marshy ground, the greenness of it all was unexpected. Ahead, the walls narrowed further to the point where the river split sheer cliffs, our eyes sliding sideways to the rocky slopes above the small gorge. We would now be forced to haul the bikes up and over, another hour of hard work before the day would be done.

It is never as bad as it looks. The ever-helpful muskoxen had trodden the best route long ago. When, after much sweating, we crested the rise and the river revealed itself again, it had widened to loop across a second, higher plain stretching back towards hills that seemed both near and distant in the depthless air – it was a second beginning rather than an ending. The patchwork of faded yellow steppe and green marshes mirrored the track of the water, speckled by the comforting dots of small groups of muskoxen. Now that we were higher, the crimson flush of autumn emerged among the green.

It was mid-afternoon, and the sunlight had begun to take on the subtlest tint of amber, an acknowledgement that time does not stand still, that everything given by the sun is soon taken away again. The air seemed too still to carry sound, but the manic giggles of loons echoed from across the water. Without saying a word, we both knew that we would go no further that day.

We looked, and we listened.